Our first impression of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina is that we were definitely in the Republika Srpska; signs everywhere told us that. On the way to Sarajevo from Montenegro, every time we crossed the sinuous border, we were reminded of leaving or entering Srpska, but I don’t ever recall a sign telling us we were in the non-Srpska part, which is the majority of the country in size.

I guess because of the terrible events of the 1990s, I was unprepared for the normalcy of the landscape, such as the amount of Srpska adventure tourism, judging by the numerous rafting outfits and camps along the Drina. Aiming for maximum time in Sarajevo, still several sinuous hours away, we were only able to enjoy a bit of Srpska culture, sort of, in the form of lunch at the Amigos Caffe, a roadside restaurant in Mješaji run by an expatriate Italian woman.

Bird life was popping in the vegetation around the restaurant. Both Gray and White wagtails flew over, and a mixed flock up in an orchard included a Common Chaffinch, European Goldfinch, Cirl Bunting, Eurasian Magpie, and several others.

As we drew closer to Sarajevo from the southeast, we saw signs to Istočno Sarajevo and monuments related to the exodus of Serbs from the city of Sarajevo to safe havens in the new Serb Republic at the end of the 1992-1996 Siege of Sarajevo. Soon after, we crossed into Bosnia and passed the Sarajevo International Airport, site of the Tunnel of Salvation, then headed east, paralleling the Miljacka River to our north. We were heading to our aptly-titled Heart of Sarajevo apartment for the night, so the route eventually took us directly down (north) through hills worthy of Tegucigalpa, across the relatively tiny Miljacka, and to a car park within a couple blocks of our lodgings, which were in the pedestrian zone.

My first impression was of pockmarked buildings, still not plastered over. With hills all around, I could almost feel the horror of nearly four years of bombardment from the longest urban siege in modern warfare. Though the 1990s death toll was a tiny fraction of what had transpired in the 1940s, it was still an atrocious event in a continent that, growing up, I, like many others, had naively assumed would never see such barbarity again (or would only see nuclear annihilation, I suppose).

Today, Sarajevo is mostly Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims), whereas before the genocides and ethnic cleansings of the 1990s, Sarajevo, like many other communities in Bosnia, was a heterogeneous mix of Bosnia Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks. Sarajevo isn’t just any old city, though: it was the jewel in the Ottomans Balkan crown, a showcase of Islamic culture at its westernmost territorial extent.

Like many Balkans cities, Sarajevo has seen it all, stretching back millennia: settlements in the region dated back to the Neolithic, then came the mysterious Illyrians, then the Romans, then the Goths, then the Slavs by the 600s CE, and eventually the Kingdom of Bosnia and even some Hungarian influence. The city itself was founded around 1461, when the Ottomans finally and decisively conquered the region and it became the Sanjak of Bosnia. Sarajevo grew to be the largest Ottoman city west of Istanbul.

After the late 1600s, Bosnia became more unstable, and by the 1800s, Bosnians were actively trying to separate from the Ottoman Empire. It became the Bosnian Vilayet under a weak Turkish presence; ethnic rivalries between the largely urban Bosniaks, the Catholic Croats, and particularly the Eastern Orthodox Serbs, were heightened, and in 1878, the Austro-Hungarian Empire invaded and conquering Bosnia; Sarajevo fell to the Habsburgs in August of that year.

The Habsburgs rapidly poured money into Sarajevo in a rush to modernize and industrialize it; one could only imagine the horror of a nearly 1,000-year-old global dynasty if they had had an inkling of what was to come, with eternal foes the Austrians and Turks both to lose their empires in the same war, just a scant three decades in the future. Today, many of the most impressive buildings are from the brief Habsburg era, though of course older buildings, particularly religious monuments to the four main faiths, are amply scattered throughout.

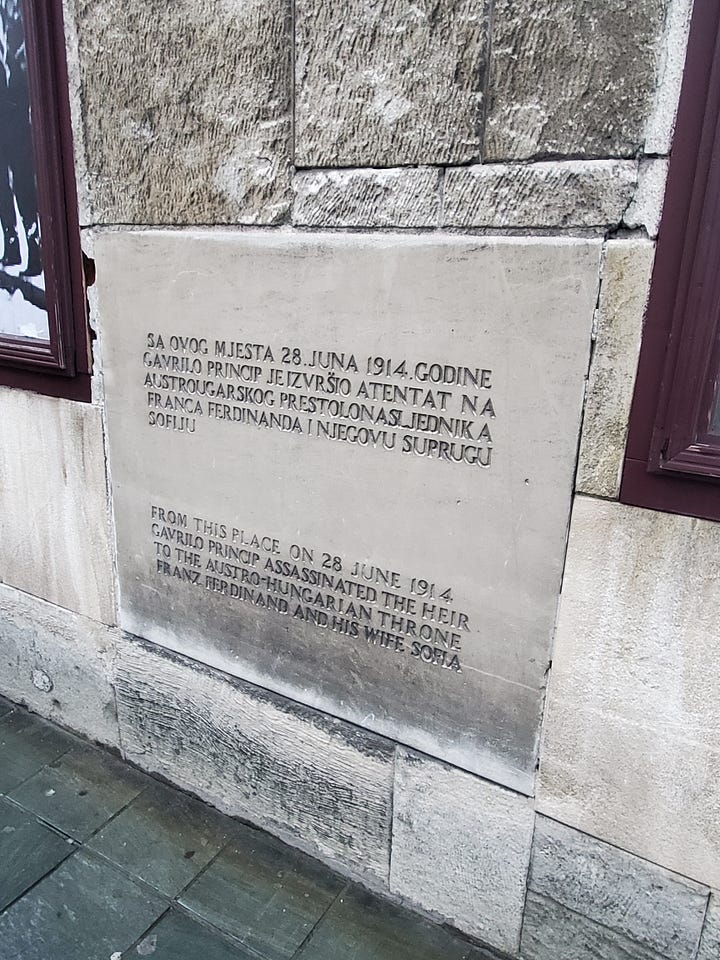

And then came 1914 and that fateful June 28 on a random street corner, well-marked today by a replica of the vehicle the Archduke and his wife were riding in when Gavrilo Princip managed to dispatch them. As soon as we got settled, I wanted to head out to the spot. In my mind, I had pictured a wide river like the Vardar in Skopje, but this one was tiny, not much wider than the Little Juniata back home, a stone’s throw across.

Not surprisingly, Gavrilo Princip is a bit of a national hero in Bosnia, or at least to the Serbian contingent. The event that revved up the bloodiest century in human history into high gear isn’t hidden from view. Of course, as I had learned before the trip started, what Princip set in motion was first known as the Third Balkan War; in the preceding several years, hundreds of thousands had already died in the first two.

Because the Black Hand was a Serbian secret society, one could be forgiven for assuming that the team of assassins and their wider network (those who were identified, caught, tried at least) were all from Serbia; they were not, and not all of them were actually Serbian. In reality, they were Austro-Hungarian citizens, not Serbian citizens, and several were Bosnian Croats, while one was a Bosnian Muslim. This has contributed to a great confusion over who, ultimately, was the force behind the event. What was for certain was that many powers were poised and ready to duke it out over territory, resources, religion, ethnicity, profits, and so forth.

One thing is undeniable: arguably the most consequential assassination in world history had the desired effect, as Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia the same day, and a few days later, their forces crossed the Sava River into Serbia, beginning the savageries that plunged the world into over four years of chaos, leaving tens of millions dead. At the end of it, Austria-Hungary, like the Ottoman Empire, disappeared. Bosnia became part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

More barbarities occurred in World War II, when the Croat Ustashe, ultranationalist Catholic fascists in league with the Nazis, took over Bosnia, wreaking genocidal havoc on Serbs, Jews, and Roma, and persecuting Muslims as well, though not with the intent of complete extermination.

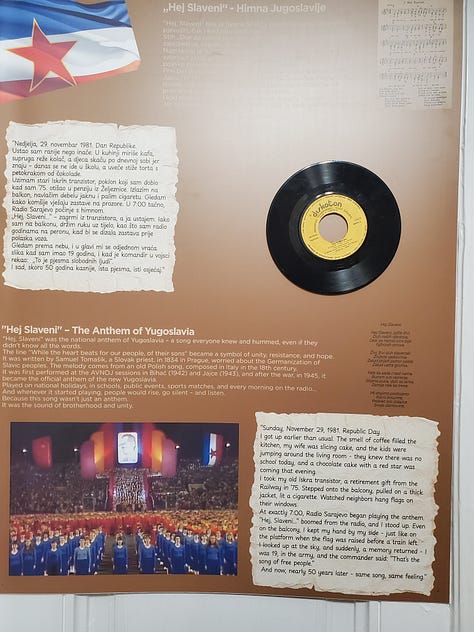

The Ustashe dream of a Greater Croatia, cleansed of other peoples, did not come to fruition, and the wounds festered for decades despite the valiant attempts of the Communists under the dictatorship of non-aligned Marshal Tito, a war hero who managed to cement the fiefdoms of former mortal enemies into a socialist entity that functioned pretty well, all else considered, until well after his death in 1980.

Indeed, even after his death cities like Sarajevo boomed, with the apogee perhaps the 1984 Winter Olympics. But the atrocities of the Greater Croatia project had not been forgotten, and communism had not been too friendly to Muslim faith traditions, either. Worst of all, Greater Serbia was still an idea in the minds of people like Slobodan Milosevic, and it was no secret that Yugoslavia was focused and centered on Belgrade and Serbia. Milosevic’s June 28, 1989 speech at the Kosovo Field to commemorate the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo didn’t help things.

And then, a bit more than a decade after Tito’s passing, it all fell apart. Naturally, Macedonia, Slovenia, and Croatia wanted nothing to do with Serbia, and got the hell out, but the problem was that many Serbs lived inside the borders of Croatia, and many Croatians lived in Serb-dominated Bosnia. Muslims lived across parts of Bosnia as well as Serbia (Kosovo). It was said that before the siege, Sarajevo was so heterogeneous that all three groups lived on the same streets, and this was one reason why attempting to create geographically “pure” zones and safe havens for these different groups involved so much coercion and violence. “Ethnic cleansing” entered the modern vocabulary, and a particularly unpleasant event, the Srebenica Massacre of some 8,000 Bosniaks by the Bosnian Serb Army, made a household name of Ratko Mladić and helped cement the anti-Serb bias that prevailed in western Europe and the US.

It is believed that true peace and reconciliation never really happened; the Republika Srpska could very well end up becoming an independent country at some point, though hopefully without further bloodshed.

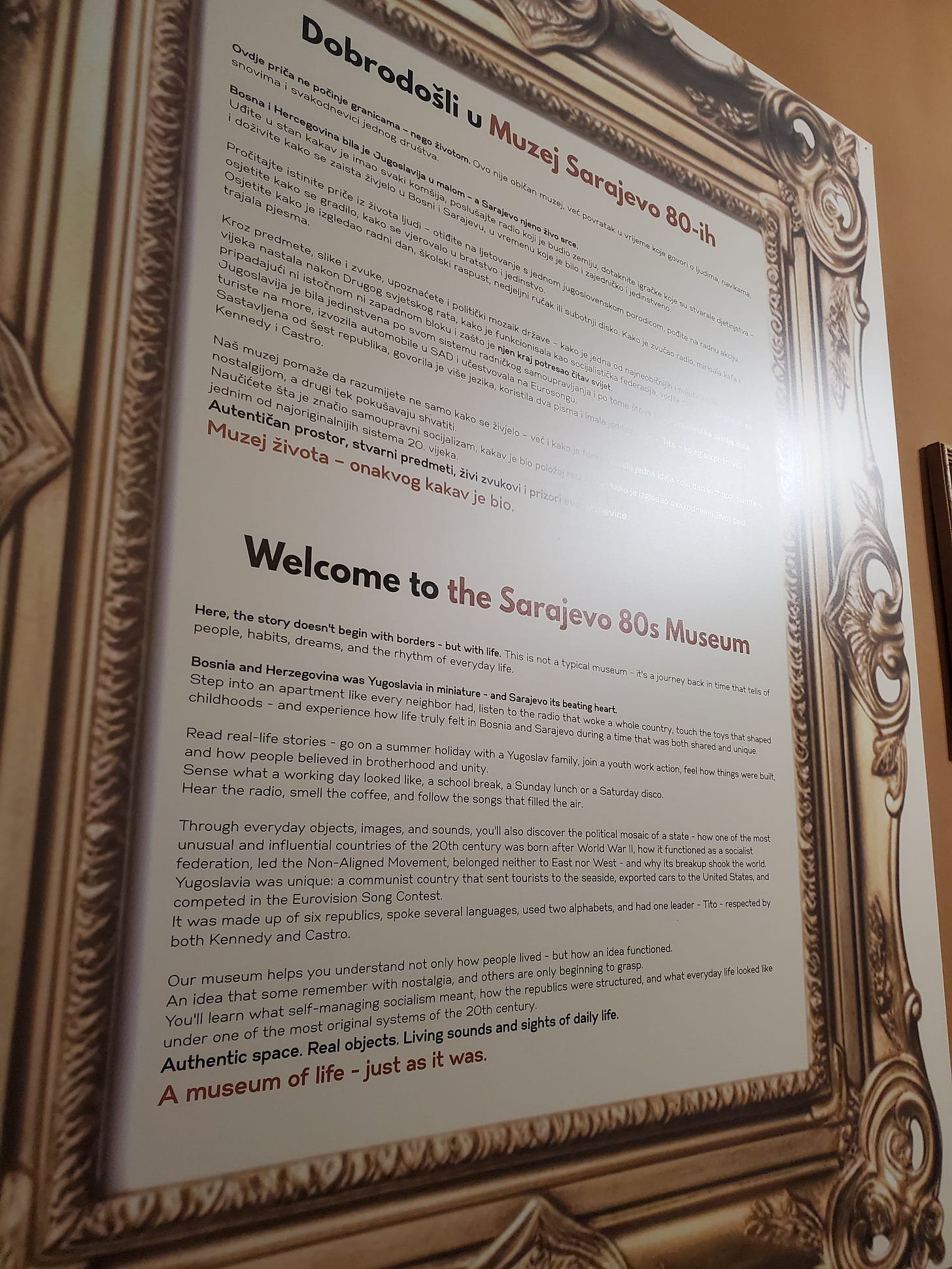

Given our own predilections and limited time, we gave the various genocide museums and memorials downtown a miss. We were more interested in day-to-day life as it is experienced today. Along with people-watching, we particularly enjoyed the Sarajevo 80s Museum, which affords a look inside a typical apartment of the time.

Paola saw many comparisons, both economically and culturally, to life in Mexico City at the same time, commenting that it helped dispel the idea she had had that Communism was universally gray and filled with suffering, with few material goods available (the way, I guess, we were all raised to believe in the West).

While the city has few non-Bosniaks left now, the cuisine remains expressive of the Muslim East, Catholic West and North, and Slavic core of the Balkans. To my surprise, we saw Hungarian and Italian ingredients in the mix, on top of the type of food we had already eaten on the trip: cuisines from Albania, Macedonia, Kosovo, and Montenegro.

The Mosque

A highlight of the visit was the Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque and associated complex of buildings and institutions, including the mausoleum of Gazi, the first ruler of the Sanjak of Bosnia, whose boss was Sulayman the Magnificent. The mosque is the largest in Bosnia and one of the most important in the Balkans; it was the first Islamic center of worship that any of of the four of us besides me had been inside. It was built in 1530 and expanded through the centuries, even thriving during Austria-Hungary’s domination, when it became the first mosque in the world to be electrified, in 1898.

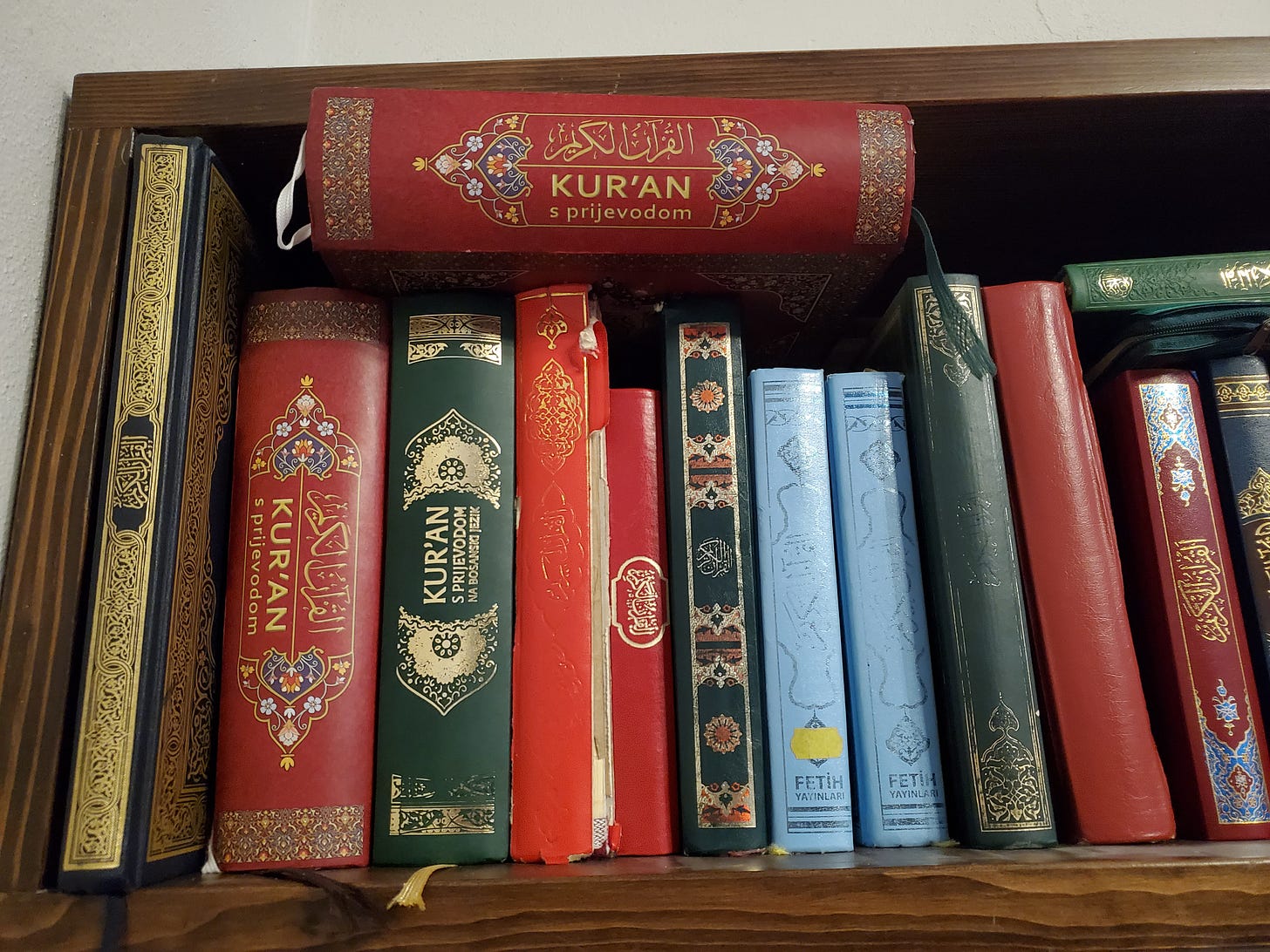

Having survived 460 tumultuous years, the mosque complex was largely destroyed during the Siege, a victim of the genocidal mindset that targets all alien cultural expressions. Thanks to wealthy (Saudi) patrons, the mosque was rebuilt quickly , and today is fully open to tourists whenever worship services are not happening. Two of us borrowed headscarves at the ticket counter, and we ducked inside for a few minutes to take in the absolute, intense silence. Korans in both Arab and Serbian were on a shelf for the borrowing.

I think my favorites parts of our somewhat enchanted evening and morning in Sarajevo were the haircut and the coffee. The latter was everywhere, both Bosnian traditional, in copper and porcelain miniatures, and myriad other ways. I commented to my daughter Eva that I didn’t believe I had ever seen a city with a comparative density of coffeeshops. Every corner? In the bazaar, seemingly every other building had one! Our favorite over a caffeine-soaked morning was a delightful barista’s corner set-up with a donation can for her aspirational trip to the Maldives - “please help me visit the Maldives” or words to that effect.

The bazaar barber we found told us the shop had been open in one form or another for a couple centuries. He personally had cut the hair of the head of the Olympic Committee back in the 1980s, as well as General David Petraeus in the 1990s. Small world, indeed!

Only the dead have seen the end of war…

A lasting impression of Sarajevo is the sadness of this lone musician in the spitting rain, fronting a genocide poster backed, bizarrely, by a “Sarajevo” written like “Coca Cola.” Take from that what you will. Someone had plastered a Free Palestine sign on top of that, testifying to the endlessness of it all. Santayana would have understood all too well, I suppose.

Nevertheless, life goes on, and despite the abundantly commemorated barbarities (better that than erasure!), we found Sarajevo to be one of the coolest, friendliest, and most interesting places any of us had ever been. Not sad at all, now, but vibrant, and still a meeting ground for the planet, if mostly through tourism these days. Ahead lay a week of Catholicism after we crossed the Sava; we wouldn’t really be back in similarly heterodox lands until the last two days of the trip.

NEXT:

The Great Divide

After leaving Sarajevo, we plodded along a two-lane truck route north for several slow hours, following the northward course of the Bosna River through the mountains on its way to the Sava, crossing back into the Republika Srpska at Matuzići. The valley was one of the most densely populated we had seen on the trip, with town after town punctuated by min…

PREVIOUS:

Durmitor!

By any measure, Durmitor National Park and its surroundings in northwestern Montenegro is one of Europe’s Top 10 wildern…