After leaving Sarajevo, we plodded along a two-lane truck route north for several slow hours, following the northward course of the Bosna River through the mountains on its way to the Sava, crossing back into the Republika Srpska at Matuzići. The valley was one of the most densely populated we had seen on the trip, with town after town punctuated by minarets on the Federation side, and Serbian Orthodox churches on the Srpska side.

We eventually left the Bosna valley and E73 motorway behind to pursue a more direct route over rolling hills to Brod and its sister city across the Sava, Slavonsky Brod. That last stretch was truly eerie, with mile after mile of abandoned Croat (and presumably a few Bosniak) houses and farms overgrown with trees and vines. These were the legacy of the Croatian War of Independence (1991-1995), evacuated residences of some of the 300,000 ethnically cleansed souls during a conflict that overlapped with the Bosnian war happening largely at the same time. Franjo Tudjman, the Croatian president, a strongman himself, was to neutral eyes on a par with Milosevic but unlike the latter he had the good sense to die before he could be tried for war crimes. Serbs were cleansed out of neighboring Croatia, so the inverse happened here.

As eerie as the miles of abandoned homes were the new structures built right next to them, and the towns with their patchworks of new and old houses, bombed out and recently off the market side by side. I suspect most of what we were seeing was the result of postwar usurpation of Croat/Bosniak properties by Serbs, but it is possible that some of the new homes were owned by Croats who have been able to successfully regain control of old properties and rebuild.

The next challenge for us was entering the European Union. Getting into Croatia, our sixth country of the trip and my 47th all-time, involved the only border hassle of the whole vacation. The border agents weren’t aggressive, but they certainly looked askance at a car with Albanian plates, and we were pulled off for a lengthy wait until they could completely ransack the vehicle and search for (I presumed) the contraband for which Albania is famous (cigarettes? alcohol? cats?). After a while, when it became glaringly obviously that we didn’t even faintly fit the profile of smugglers, they waved us forward, and thus we passed the biggest test yet of our green card magic entry certificate. On to Croatia!

Slavonsky on the Sava

The Sava was the largest river we’d seen yet on the trip, and was fittingly wreathed in marshlands on the Bosnian side, with gulls and cormorants all about. It’s a tributary of the Danube to its east, and is most famous as a border between Islam and Christendom over the course of several centuries.

Slavonsky Brod is best known for the gigantic Fortress of Brod, the ruins of which, some reconstructed, take up a fair portion of the center of the city. The Fortress was built by the Austrians in the 1700s as a bulwark against the Ottomans across the Sava, though ironically, despite centuries of regional warfare, it was never really useful in times of conflict. Nevertheless, what is left of it is a stark symbol of the massive ego of the Habsburgs, that inbred, landlocked clan who always seemed to be at or near the center of major European dramas.

Our apartment for the night was, as usual, a small challenge to get to—not the location itself, which was obvious, but the precise fashion we were supposed to park and access it. After a bit of drama, we found ourselves in the most modern privately-owned apartment of the whole trip. As usual, we were right next to the main pedestrian zone, which, though mostly abandoned that cold and windy evening, with few restaurants open, was hopping the next day. Local folks were somewhat bemused to see us, as Slavonsky Brod, though not an unattractive place, isn’t the type of tourist haven that foreigners tend to flock to.

We stopped in at Grill Master Big Mamma for some Croatian fast food to go. This was a new experience for us, as hitherto our one-country-per-day rhythm had spurred us to seek out the most traditional cuisine we could. Croatia was another story, though: we would have nearly a week in and out of it, all told. There would be plenty of time for Croatian tradition; tonight was fried things and delicious grease, a good American tradition in itself.

The portly cook/server/possible owner, whom we took to be Big Mamma her/himself, was garrulous, with fluent English, and one of the friendliest and most welcoming people we met on the trip, which is saying a lot. Back at the apartment, we choked it all down with generous servings of our accumulated auto-bar (not seized at the EU border), wine and rakija from several countries, I think, and, as always, whatever the local beer was.

The Rookery and the Fortress

I was up before a breezy, frigid sunrise to bird along the lengthy river promenade. A rookery of at least hundreds, and possibly thousands, of Hooded Crows and Eurasian Jackdaws, with at least one actual Rook mixed in, erupted from the trees above me and ebbed and flowed above the river, as increasing numbers of Black-headed and Yellow-legged gulls showed up to start fishing. A Common Buzzard (Buteo buteo) was also about, as well as two of the jewel-like Common Kingfishers. At several points I flushed Gray Herons, and six Great Cormorants were swimming and diving in the turbulent waters where a subterranean stream from downtown dumped in.

After exhausting the walkable part of the promenade, I doubled back by the Fortress, passing a memorial to 1992 war dead, then a corner of the unrestored fortress, then a sign commemorating the fall and subsequent massacre at Vukovar, a Croat stronghold that fell to the Serbs around November 18, 1991.

From Slavonski Brod we drove west and north through flatlands and rolling hills on the best and easiest roads we had seen since Albania. This eastern portion of Croatia, not unsurprisingly heavily contested throughout history, is known as Slavonia, supposedly the most “backward” of the country’s three major regions, after the main central portion (Croatia proper, so to speak) and Dalmatia, the resort-soaked coastal part. We were, as usual, in a hurry to get to the next country, which in this case was Hungary (#48).

No time for Liberland

With a few hours to spare before our main destination of Pécs, we decided to whoop over to the Danube itself. Sadly, there was not enough time to plumb any of the micronations that line the Danubian border between Serbia and Croatia, true patches of terra nullius that enter the news cycle now and again whenever some bitcoin-backed fraudster decides to attempt to set up camp in a willowy river bottoms to prove to his online “citizens” that his principality actually exists. These attempts are usually nebulous and short lasting, but provide enough fodder to raise enough money to…whatever. The pockets, such as Liberland and the Free Republic of Verdis, if they were to really become states, would make Andorra and San Marino look gigantic by comparison; like most such places, they will no doubt some day be parceled off between Serbia and Croatia.

Swamp creatures

Our first stop in Hungary was Mohács, high above the Danube, internationally famous—or infamous, depending on one’s experience—for the Busójárás, a winter carnival straight out of legend. From what we learned, the town, like a miniature New Orleans, is single-mindedly focused on pulling off a festival that involves all manner of debauchery and outlandish costumes. Those wearing the costumes are the busós, who have license to get away with a fair amount of harassment, or so we were told.

The best we could do at this time of year was find a shop that sold a few refrigerator magnets of the apparitions, as we had a pleasant stroll about the downtown. As a first-time visitor to Hungary (Paola had been there before), I was also pleased to confirm a stereotype: Liszt is the type of European superhero they put plaques up for if he slept there, as he had in Mohács on Oct 27, 1846.

Then we were off the 30 minutes back west to Pécs, Hungary’s fifth-largest city, site of an ancient university, and a famous destination for fine porcelain and leather shoppers. This time, we got to stay in an actual hotel at the edge of the old town and park in its lot, a rare find in our budget range.

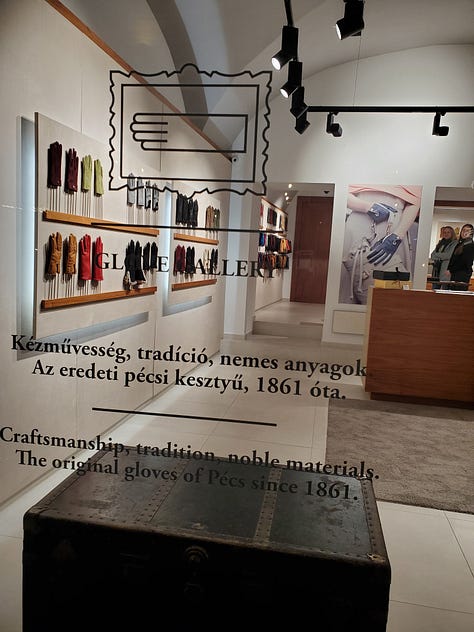

The city is outstandingly attractive; my brief impression of Hungary overall was of a place that would be impossible to confuse with anywhere else, not least for the mixture of an out-of-place language brought from far to the east by the Huns and a Catholicism straight from Rome. We roamed about for hours in the spotlessly clean streets, and Paola was able to buy a little of the porcelain as well as high-quality leather gloves. We dined in a recommended restaurant, washing down a meaty Hungarian feast with abundant unicum, a liqueur that I became quite fond of. It is reputedly made with some 40 herbs, according to a secret recipe.

Paola and I had a somber moment at the gorgeous Synagogue of Pécs, built in the mid-1800s, managing to get in not long before it closed and buy a self-guided tour. Very few Jews were left in the city after the Holocaust; most died in Auschwitz, but a few still use the synagogue, which functions more as a cultural icon and remembrance site than anything else.

Less somber were the decidedly non-traditional signs in our dinner restaurant’s bathroom. Perhaps a fitting reminder that we were, quite temporarily, in central Europe rather than the Balkans?

A reminder of 1956

Pécs sits at the southern edge of the Mecsek, a range of wooded limestone mountains that reach slightly over 2,000 feet in elevation, part of the Trans-Danubian Hills region west of the Great Hungarian Plain (which, to my regret, we never saw). The next morning, I took a bracing hike to the top of the first hill in the range, dodging the switchbacks of the road to follow a maze of forest paths through the combined nature park/watershed area. This was to be my main chance at a Hungary bird list, and the woods did not disappoint.

At first light, the thick landscaping around the small mansions along the approach sheltered Eurasian Blackbirds, Goldcrests, European Robins, Black Redstarts, and Spotted Flycatchers, common dawn callers that seemed to be in every European forest. Farther up, as I reached the top, I saw a Great Spotted Woodpecker and hordes of chickadee-like Eurasian Blue Tits, along with Long-tailed, Great, and Marsh tits.

The woods also contain restored stone works that seemed to be associated with the park’s function as a water reservoir. On one wall was a memorial to the local 1956 resistance, part of the doomed Hungarian Revolution against the Soviet Union.

Not far away, I found a small stone tower with a staircase spiraling down into gloom, and a pair of sandals left out for some reason. I began to descend with the light of my phone, but heard loud protestations, something like “get out!” in Hungarian; this was someone’s rent-free lair, it seemed.

Ultimately, I got what I came for on my brief hike, a view southward across the city to flatter parts of the Carpathian (Pannonian) Basin this side of the Drava River, more or less in the direction we would take a bit later in the day.

NEXT:

PREVIOUS: