I wasn’t wrong. As I trudged up First Field’s gloom sometime after 6 AM, the wind at 34 degrees added flakes to the fragile white coating. (Back in Tyrone, all is still brown.) “Zephyr?,” I wondered.

Wikipedia confirms: Zephyrus was a Greek deity that announced himself in the west wind. He’s here, tormenting the weaker, bendy spruces while leaving the stronger ones alone. There’s one spruce in particular that sounds like a fleeing Mourning Dove.

As I arrive at my sit spot, right at 6:30 AM, two Barred Owls erupt from the tall spruce above, practically becoming entangled in other as they wing noiselessly off toward Laurel Ridge. On Thursday, Dave heard the familiar “Who cooks for you?” vocalization at dusk from up here. In a couple months, they’ll be nesting somewhere in the vicinity, I hope.

First Act

Last weekend, down along Bird Count Trail, it was in the teens and clear when the first White-throated Sparrow ‘seep’-ed at 7:01. I was hoping for something similar here, but the overcast mountaintop stays silent.

It seems trite to say the mountain feels “expectant,” but nonetheless it is some considerable consolation that there will never be a silent dawn: something bird-ish always makes a noise. But by this time in January, it’s a stretch to call it a “chorus.” And don’t think it’s dead silent here even though it’s in the middle of the wild: we’ve got an interstate below and a 180-degree sweep of train noise, from Bellwood’s direction back behind me, around through Tyrone in front, and then all the way to the Short Mountain tunnel by Spruce Creek. There always seems to be at least one Norfolk Southern train rumbling somewhere along that stretch, or even along the old track from Tyrone to Lock Haven.

Today, a Common Raven is the first diurnal bird to vocalize, croaking four times at 7:05. Then at 7:08, the faint clanking of Song Sparrows, down in the brush around the neck of the field. Other Song Sparrows, and a White-throated Sparrow ‘seep.’ A faint series of announcements follows, including just a few birds from the spruce grove: the two sparrows, a Dark-eyed Junco, maybe 10 individuals in all.

Another gust—the last, it turns out—rustles most of the movable spruce tops. The ticks and chips die out after ten minutes.

Second Act

At 7:17, the noise starts up again under a leaden sky with no hint of sunrise. White-throats, Song Sparrows, a Northern Cardinal, mostly from the black locust thicket. A hesitant Carolina Wren. Quiet again by 7:23, but for a distant American Crow. The silence rolls back in.

Third Act

Something has got to happen soon. The crows aren’t having it; they’re cawing from different directions at distinct pitches. Distant White-breasted Nuthatch, and maybe a Black-capped Chickadee, far off. 7:33 AM.

Finally, the dawn gets underway when the first of many chickadees lets loose with a ‘dee-dee-dee’ loud and close at hand on Laurel Ridge. Crows keep at it through a light pellet ice. The zephyrs are gone, though.

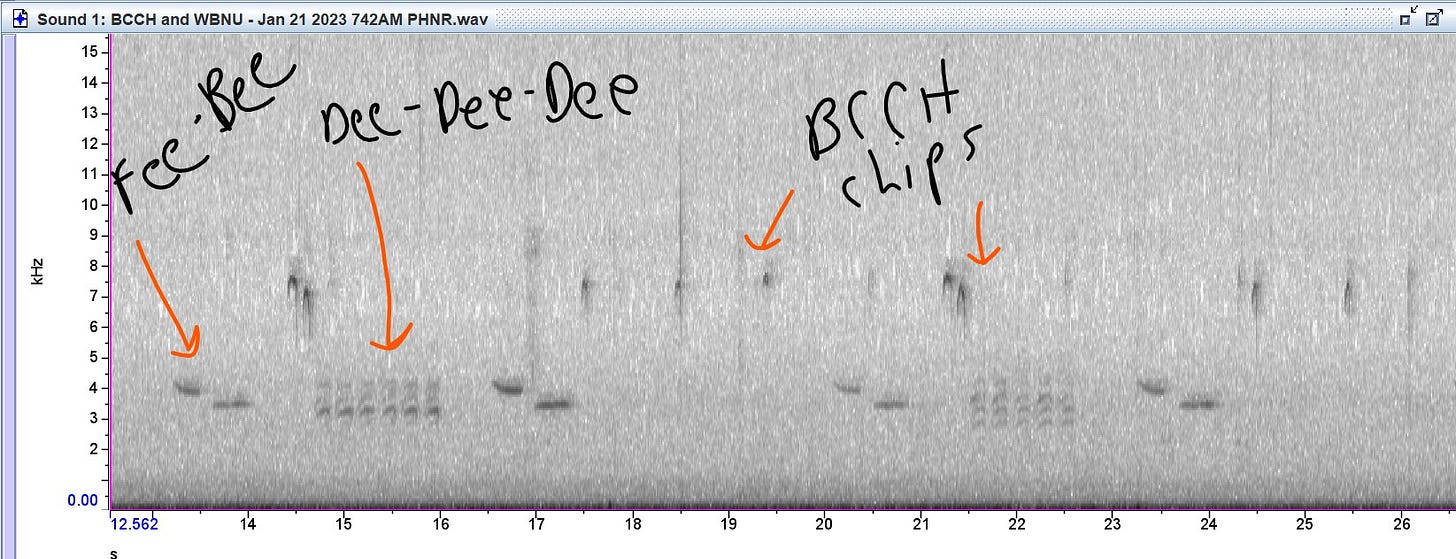

An Eastern Bluebird calls, and then another, overlapping, around 7:42, as chickadees and nuthatches take over the spectrum (listen HERE). I hear six distinct chickadee vocalizations.

A Carolina Wren down-trills; six starlings rush overhead, commuters to town.

But that’s it. Not a woodpecker to be heard, and the sound again drops to nothing. I head to Far Field.

Valley Swing

The Far Field is a mountaintop meadow at the far southern end of our property, overgrown with goldenrod, black locusts, and barberries. I’ve never done a dawn sit there, but it always has a little bird population of its own, with at least a dozen White-throated Sparrows. The Far Field is just a few minutes’ walk along the ridge: at the spruce grove Sapsucker and Laurel have effectively joined into the single crest that heads north to Altoona, gaining elevation with every fault. Here, just above the Far Field Fault, the Tuscarora crest reaches a bit more than 1700 feet above sea level, some 800 more than the Little Juniata at Tyrone.

Back here, cell signal dies out as the aspect tilts toward Sinking Valley. Train noise dwindles as well. The hotspot extends into a series of thickets and hollows that plunge down between the valley-facing benches of Bald Eagle sandstone.

Nothing much but the white-throats and a curious Hairy Woodpecker up here, so on the spur of the moment I decide to head down Far Field Hollow and come back up Roseberry Hollow, describing a loop that will take me the long way back to the spruce grove. The fringe of valley might be good for a Yellow-bellied Sapsucker or a Northern Harrier.

A lone Pileated Woodpecker, some of the same January species I’ve already detected today, and a screeching pair of Red-tailed Hawks are all I find, however, at the cost of being ripped by multiflora roses. The invasive thickets here are dense, but nothing new seems to be about.

The habitat contrast back up on top when I cross onto our property again is profound. Ours is a woods that has been managed to reduce white-tailed deer numbers and leave old trees and vines alone. The deciduous forest here is richer, taller, older than on neighboring properties—but this time of year, even the surfeit of large black cherries, oaks, and other economically valuable species we haven’t touched isn’t enough to make an appreciable difference in the amount of birdlife.

Epicenter

Even First Field’s goldenrod and fringing brush piles aren’t enough by this time of the winter. All the action—as usual—is around the houses, where the feeders are. Twelve House Finches here, and four American Goldfinches, whereas there were none of either species in the woods. A boisterous mixed flock with Downies, a Hairy, and a Red-bellied Woodpecker, many of the ‘TCN’ trio (chickadee-titmouse-nuthatch), an American Tree Sparrow, two Mourning Doves, even a lingering Field Sparrow around the spring house cattail marsh. This is in addition to Song Sparrows, White-throated Sparrows, Dark-eyed Juncos, Northern Cardinal, Carolina Wren: pretty much everything I found elsewhere. Not all of them even bother with the feeder: safety in numbers, I suppose, with three species of owl and two of Accipiter on the prowl.

Down the mile-and-a-half of Plummer’s Hollow, not a call, not a bird. Same at the river. The feeders and my balcony are two of the three main poles of activity in the hotspot by the end of this third week in January. I’ll check the hidden pond tomorrow morning to kick off the Plummer’s Hollow 200 - Sprint # 4. We’re still at 55 species, and still without any of the winter specialties. I’m glad I didn’t factor them into the Big Year expectations.