Highlights

Global Big Day: #31 among US hotspots (# 2 in PA)

Black-crowned Night Heron (NFC, Mon PM)

American Coot continues (Tues AM) but Yellow-breasted Chat disappears

Flock of 175 Cedar Waxwings (Tues evening)

Mourning Warbler (Fri AM)

Ring-necked Pheasant (Sat, heard from ridgetop

Common Nighthawk (Sun AM along tracks & river)

Prairie Warbler (Sun PM in field)

Log

May 20 (Mon). AM: 69 spp. (2-mi. hike and drive, 2 hrs.); PM: 54 spp. (5-mi. hike, 2 hrs. 35 min.)

May 21 (Tues). AM: 43 spp. (1.2-mi. hike, 1 hr. 15 min.). PM: 24 spp. (balcony, 45 min.)

May 22 (Wed). AM: 62 spp. (3-mi. hike, 1 hr. 30 min.)

May 23 (Thurs). PM: 33 spp. (balcony, 1 hr. 30 min.)

May 24 (Fri). AM: 50 spp. (2.5-mi. hike, 2 hr. 30 min.)

May 25 (Sat). PM: 65 spp. (2-mi. hike, 2 hr. 30 min.)

May 26 (Sun). AM: 51 spp. (1.2-mi. hike, 2 hr. 15 min.); AM/PM: 37 spp. (0.25-mi. hike, 30 min.)

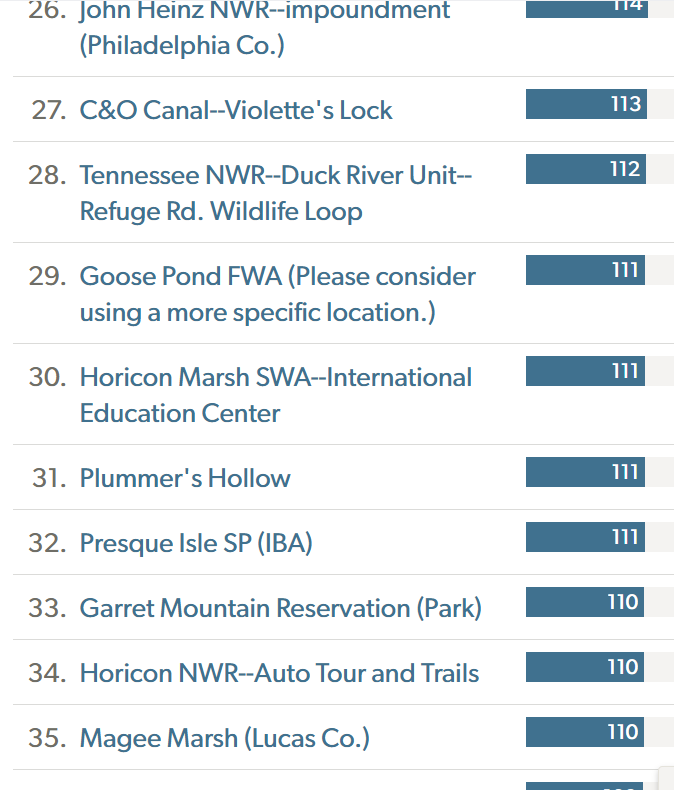

I joined 63,219 other birders across the world on May 11 for Global Big Day, during which 7,725 species were reported to eBird. Plummer’s Hollow’s total of 111 species was modest by global standards, but enough to tie for second-place in Pennsylvania hotspots and attain the 31st spot in the US. In the past, a few birders have participated in Plummer’s Hollow’s Biggest Weekend, and I think next year this needs to happen again in an all-out, midnight-to-midnight effort. Here’s this year’s top 10:

With multiple birders across the hotspot, and a few NFC recorders to boot, could we make this list in 2025? Across the whole weekend this May, 125 species were recorded for the hotspot, but it was certainly not an all-out effort. I think we could crack the top 10.

Today (Monday) or tomorrow will be the chat’s last day. He has stopped singing at night, and on Wednesday, he won’t even sing during the day. Mom’s Merlin might still pick him up down in Roseberry Hollow in a couple days, but he won’t be back to the blackberry patch. One wonders whether the highly territorial and aggressive pair of Sharp-shinned Hawks nesting in the spruce grove not far away did him in or drove him off, or maybe he fell prey to something else. Perhaps more likely, he simply never had any success attracting a mate—it’s not been a standard chat location for decades, after all.

The rest of the breeding species appear to be doing just fine, thank you. Well before 5 AM, a group of Purple Martins from colonies in Sinking Valley hawks insects in the sky above First Field.

In the cavernous depths of the Hollow, Acadian Flycatchers, Louisiana Waterthrushes, Wood Thrushes, and Scarlet Tanagers echo clangorously all around, reaching a crescendo before 5:30 AM, and then ebbing a bit. A breeding species that seems easiest to detect at this hour is the Northern Parula, which sings from three locations before fading away as American Redstarts, Ovenbirds, Worm-eating Warblers, and Blackburnian Warblers take over.

Up on the powerline, above a sea of fog, Merlin tells me that what sounds like a Chestnut-sided Warbler is actually a Common Yellowthroat, but until I see the masked male singing from a wire I don’t believe it. Warblerers aware! There is a certain blending of songs between species; at some points the buzzes and gasps sees almost to form a continuum, with the ever-confusing redstart filling in the gaps, sounding now like a Black-and-white Warbler, now like a Bay-breasted Warbler, now like a Yellow Warbler. Males and females are singing to (or at) each other, increasing the complexity even more.

By 6:30 AM, the list is already over 50 species and bird activity is beginning to slow. In the yard, a small flock of Blackpoll Warblers, the tail end of transient migration. This explains the high numbers of zeep calls on the NFCs.

In the evening, I watch a Great Blue Heron winging to roost or to a dusk feeding spot, flapping along the line of Bald Eagle ridge toward the Gap. Unexpectedly, it takes a sharp right and gathers itself into a tight dive, hawk-like, disappearing below my line of vision against the side of the hill, somewhere by the highway. It’d well away from any body of water, so I can’t imagine what it’s after.

Tuesday

A Black-crowned Night Heron went over last night a bit after 10 AM—second of the year, and second ever. Then, around 2 AM, yet another Yellow-bellied Flycatcher, on its way to some northern bog.

Well before 6, I watch a Chimney Swift spiral down the heavens and then tucks its wings as it drops vertically into a brick chimney up the block. It has already been on the wing some 20 minutes - does this mean it is returning to nest with food for a nestling?

Later, we hit the tracks for a brisk jaunt to the pond, where a Green Heron takes off. Quite unexpectedly, the stranded American Coot is still puttering about below the bridge, day 10 of its unusual visit.

Waxwing Invasion

Not long before 8 PM Tuesday evening, a flock of around 175 Cedar Waxwings coalesces above Bald Eagle Creek and heads off through the Gap. These seem more like fall numbers, and certainly well above the quantity we’ve seen in May the last few years. Then, after the sun hits Sapsucker Ridge on Wednesday morning, I see scores of waxwings buzzing about the tops of the black cherries.

The chat is absent for good on Wednesday, but the Golden-crowned Kinglets are still around, nesting in the shadow of the sharpies, somewhere deep in the Grove, their calls barely audible. A bit later, a Hermit Thrush clucks from its favorite winter patch—now year-round?—to the left of the powerline. This is late for the species, which always acts like it wants to breed but then fades away northward and up-elevation under the onslaught of Wood Thrushes. One of these years!

The night chorus, if you can call it that, is still impressive, even in the absence of the chat. The NFC mic picks up both Yellow-throated and Red-eyed vireo song phrases, clear and crisp enough to signal that they’re singing in migratory flight rather than from locations in the trees. A Common Nighthawk peents by as well, as do the typical parade of thrushes. The most frequent local nocturnal singers are Ovenbirds, Field Sparrows, Eastern Whip-poor-wills, and both Black-billed and Yellow-billed cuckoos, and high May also coaxes others to sing throughout the night. Common Yellowthroat, Song Sparrow, Gray Catbird, Indigo Bunting, and Northern Cardinal all play a few bars at one point or another from local perches, while Scarlet Tanagers and Rose-breasted Grosbeaks sing, and like the vireos, it sounds like they might be in flight. Not be left out is a local Eastern Wood-Pewee, who mourns every few minutes throughout the hours.

Around 10:18 PM on Wednesday evening, any listener in the field would have heard a congregation of Green Herons doing God-knows-what overhead. Is this a migrating group, somehow? I’ve never recorded so many calls over such a length of time. I associate the species, when they’re not migrating, with quick and low flights, but unless this is many different birds on the move, they were detained by something. Did they alight in some marshy bit of the field, for some reason?

The night oddities continue with the first NFC of a Great Crested Flycatcher around 4 AM on Thursday.

The Wind-Down

A warm and humid Thursday evening is perfect to witness the return to roost from the balcony. Around 7:30 PM, a rare sight: Scarlet Tanager, right overhead, then plunging into the woods on Sapsucker Ridge. Returning from a foraging expedition on Cemetery Hill, perhaps? Moments later, an Osprey dives into the Gap—another unusual sight by this late in the month. I wonder where the nearest pair is nesting?

The parade of small wonders continues with a quartet of Purple Martins above the interstate, looping about, heading out through the Gap. I’ve not seen local martins returning to roost from this side of the mountain in recent years, and combined with the growing amount of pre-5 AM calling over the top of the mountain, I wonder if breeding numbers in the Sinking Valley colonies are up (again) this year?

The swallows stake out their spots on the wires, and a bit after 8, the Carolina Wren starts its evening song. It’s hard to believe I was ever missing Yellow Warblers—they’re louder than ever this year, and right now two are singing at each from the sycamore tops. Male and female?

Around 8:40, there’s a rapid die-down of activity as the last swifts, swallows, and waxwings whizz down out of the sky, and cardinals sing a few more notes. Then, it seems like only robins are left by 8:50, but at 3 minutes until 9, a crackle issues from the riverbank—the catbird, getting in a few more meows before calling it a day. That leaves only robins, but even they wind it down across town by five after. Last of all, a vocal flock of Canada Geese ends the evening at 9:06.

Strippers

Something is up with the Great Crested Flycatchers and cuckoos this year. On Friday, a dawn circuit around the field and woods kicks up six of the former and five Yellow-billed Cuckoos. The latter don’t tend to sing much at an early hour, perhaps fatigued after calling off and on through the night. Some other odd sounds down in the Greenbriar area are a possible sapsucker drum, but it could just be a red-bellied, and I’m in too much of a hurry to try to find it. One surprise, around the thickest, jungliest area of hillside springs, is a Mourning Warbler.

On Saturday morning, I’m parking at the barn at ten to 5, and the first bird out of the gate is a Great Crested Flycatcher from down near the wetland. I don’t recall hearing this species’ dawn song very often in the past.

Up on the powerline overlooking Sinking Valley, a Brown Thrasher sings, and whip-poor-wills call from two directions. A House Wren gurgles faintly from below—a species that appears to have given up nesting in the field this year, once again.

Most of the year, American Crows would be among the earliest species, but today, it is number 28, overheard all the way at the late hour of 5:27 AM. A Yellow-billed Cuckoo starts chuck-ing from close at hand, and then a Mourning Dove lands on the wire above me, all loud wingbeats and cooing. After a minute or two, it does a display flight out into the valley for a quarter mile, then soars back into the canopy.

And then, a sound I haven’t heard from the hotspot in many decades: the keek-kuk of a Ring-necked Pheasant from the edge of the valley somewhere. The last record was a note in Mom’s journal about one detected on November 4, 1999. In those days, the species was still considered wild and countable; today, it is classified as an escapee, so it won’t form part of the year’s total.

By 5:49 AM, 40 species are on the boards, though the total won’t go much higher at this spot. A Great Crested Flycatcher, unconcerned with my presence, flies across at 6 AM and alights in the sunlight that is touching a snag along the edge of the cut. Silently, it begins hawking insects from the air, and after a few moments, it moves off.

I head north along the top of Laurel Ridge, accompanied by the gentle rain of frass from spongy moth caterpillars fattening on this year’s leaves, which are already half-stripped. The oak deadenings are alive with Hairy Woodpeckers.

Along Ovenbird Trail, a new connector route down to the Forks, I flush—what else?—an Ovenbird, which flies low and fluttering, stopping to drag its wings and lure me from its nest.

With little effort or time, I detect five Yellow-billed Cuckoos before seven, and then the nearest Black-billed Cuckoo sings above the barn. A ratio of 5 to 1 is about right. Today, it’s eight Great Crested Flycatchers in a small part of the property, and the ever-present reeps bring back memories of the 1980s. Far, far more are in the hotspot, no doubt, and yes, they, and the cuckoos, have come for the spongy moths, as they did back then.

After 5 PM on Saturday, we are pummeled by one of the most savage lightning storms in recent years, accompanied by a tropical quantity of rain. I watch as lightning strikes the point of Sapsucker Ridge, and wonder how close we are to a downburst or even a tornado. I learn two new things. As I’m staring up into a brighter patch among the roiling clouds, I pick out three Chimney Swifts hawking for insects, moving at unimaginable speeds, seemingly unfazed by the thunder and lightning. That does it: they’re now at #1 on my mental list of Top 10 most bad-ass local birds, a reputation cemented not only by this behavior and the rest of the aerial maneuvers but also by the countless times I’ve watched them chase after every manner of nest predator, undeterred by size or reputation.

The second lesson is that cats—or at least our cat—seem unconcerned by thunder. Pepe manages a somewhat quizzical stare at us as we flinch from the nearest strikes. A motorcycle revving its engine will send him for cover, but that’s pretty much it.

As the storm churns off eastward, and the rain continues, a frenetic Yellow Warbler starts right back up singing, and the swallows land on the wires again. Ah, May!

Fog, Bullfrog, Bullbat

All the rain is bringing out the insects en masse, which is good for the birds and good for a lot of other biota as well.

On Thursday morning around 4 AM, the antenna picked up a gray treefrog, which could be a first for the mountain. On Sunday, I’m at the pond, listening to an American bullfrog, as the last spring peepers fade. I’m looking forward to last night’s NFCs, as I heard a small group of Swainson’s Thrushes peep over around 5 AM when I was walking over from town. The weather was right, and it’s been awhile since the last good night flight.

The fogged-in highway through the Gap is quiet enough that I can hear the pewees starting up on the other mountainside, as a Green Heron calls overhead. Northern Rough-winged Swallows are already about in the darkness as well. Soft Baltimore Oriole notes, and then a robin that sounds almost like a phoebe.

A bit later, in a bit of daylight wrapped by fog, a large, swift-like shape flaps quickly overhead, circling the pond before heading off to the river. Common Nighthawk, out for the gathering clouds of bugs in the air. A few minutes later it reemerges, going upriver, and I see it yet another time before it’s gone. A pair of Wood Ducks flushes from the duckweed at the west end of the pond and wings off toward the valley, squealing. For all I know they could be nesting up on Sapsucker Ridge, as they’re wont to do; it’s rare to see them at all this time of year.

On the way back, a male House Finch, of all things, perches on a snag in Redstart Swamp and sings his beautiful song over the numbing chatter of redstarts. I walk up the Hollow a bit to round out the list, and Merlin alerts me to Hermit Thrushes. They’re not, however; the sound is alarm calls from the considerable Wood Thrush population, warning everyone of my presence, I would guess. I realize they’ve been at it since I entered the woods.

Around noon, I drive up to grab last night’s recordings, in anticipation of a big flight. Alas, yesterday’s storm knocked the system out—and with the loss, the chances of catching a few species for the year (ones we’ve never picked up going southward in the fall), such as Willow Flycatcher and Eastern Kingbird, is rapidly fading.

During the time I go into the garage to get the recordings, I tend to let Merlin run on the phone out in the gravel. You never know. This time, when I go out, miffed by the loss of data, I glance at the bird scroll, and it shows a Prairie Warbler. Unlikely, I think—the A.I. tends to select Prairie every so often when it hears a Field Sparrow or Cerulean Warbler. Indeed, the local Cerulean, which I can see moving about in the walnut branches, is next on the scroll. I’m about to head out, when something that doesn’t sound quite right sings from the edge of the powerline cut, a wavering, upward call that always seems to embody the essence of summer heat to me, though I have no idea why. After a few more times, I can tell that it’s certainly a Prairie Warbler, quite unusual this late in the season for a species that doesn’t breed in the hotspot.

I go gingerly toward where it’s calling, but it’s already gone, appearing to have moved westward along the cut. Then it calls from the upper side of the field, again along the cut. I would presume it’s low down, but perhaps, as I occasionally see in migration, it is high up in the trees somehow. Whatever the case, it stops calling and I don’t hear it again, and the chorus goes back to Field Sparrows. Though it might just have been a late transient, it could also have been an individual still looking for somewhere to set up a breeding territory.

AUSTRALIAN INTERLUDE — We’ll be in the Northern Territory for awhile. I expect to write the next entry here in about a month.