La Niña came, as I thought she would, deathly white and terribly cold. Snow squalls have come and gone throughout the month, and high winds, and heavy rains. Sitting here in the pre-dawn Christmas Eve, suffering another season of endlessly repetitive piped Christmas carols—they go all night in downtown Tyrone, where the inconsequential live—I’ve finally found time to wrap up the year. First things first.

Mike’s timely demise

The refurbished laptop cracked apart, its brittle components dying in the teenage cold, on some dark and stormy December night, but the antenna had long since died. It had been emitting death rattles for some time already.

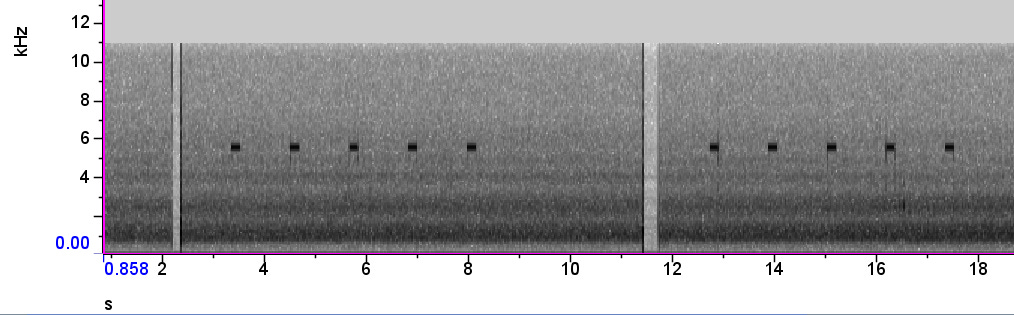

The antenna showed up one late pandemic summer day in 2020, but it took until October to figure out how to get all the correct gadgets and hook them up. Right out of the gate on its first night, October 14, it picked up a Savannah Sparrow, a Plummer’s Hollow first that we hadn’t been able to detect in over 50 years of daytime birding. A few days later came the first Grasshopper Sparrow, and then in November, the first detected Horned Lark, Greater Yellowlegs, and Snow Bunting flew over. We moved away after that, but I returned to set up the antenna during a few nights the following May: Virginia Rail, Bobolink, Semipalmated Plover, and Pectoral and Least sandpipers.

The following spring, an irascible gray squirrel who owns the barn chewed through the microphone wire multiple times, with several successful surgeries by Paola not enough to keep its jealous wrath from destroying what I had planned to be the first complete recording season. I finally hoisted the white bucket to the garage roof, and recorded off and on from June to November.

Eleven new species were added to the Plummer’s Hollow list in 2022, nine of which were NFC-only: American Wigeon (Mar; since also seen), Common Tern and American Bittern (Apr), Lesser Yellowlegs, Dickcissel, Least Bittern, and Semipalmated Sandpiper (May); Black Tern (Jul); Dunlin (Oct).

Finally, during the Plummer’s Hollow 200 in 2023, the antenna, undisturbed on the garage roof, got a new (refurbished) laptop, and Raven ran 24/7 from late winter to late fall. The new species continued: Wilson’s Snipe and Ring-necked Duck in March, Sora, Common Gallinule, and Caspian Tern in April; Henslow’s Sparrow, Whimbrel, and Ruddy Turnstone in May. By this time, the outlines of the night were taking shape—what tends to fly at what time during what weather in what season. The last species to bed and the first to rise were also perfectly tracked, the sequential parade of locals rising, flying, perching, feeding, distinguishable from but often mixed in with the last flight calls of the long-distance migrants.

It became possible to know—with better precision than daytime alone allowed—when spring migration finally ends and when the “fall” begins (early July, for shorebirds). In 2023, a Short-billed Dowitcher, presumably heading south, flew over on July 1. In August, a quiddyquit (Upland Sandpiper) added yet another new species, and the true fall brought the first American Golden-Plover and Black-bellied Plover. By this time, my lifelong love of the katydid chorus had turned to despair, as it blacked out the spectrum during the height of migration, though a few chilly nights allowed some appreciation of the nearly endless river of thrushes—Veeries, Swainson’s, Wood, Gray-cheeked, and finally Hermit, stretching from July all the way to November, breaking state numbers records, sometimes thousands per hour, sometime plummeting into the trees all around as the first towhees called, at other times zooming by my face.

This year has further refined my understanding of the ridge-and-valley night, with first-ever American Coot (later seen as well), Black-crowned Night-Heron, Willet, and Red Knot. Even American Barn Owl, which has disappeared from view in eBird, has become a regular and predictable migrant flyover. All told, of the 42 species added to the Plummer’s Hollow list since that first October night in 2020, all but six were thanks to the NFCs.

What flies through the sky on a December night?

The antenna held out until the evening of December 11, recording three weeks beyond the previous years. As expected, the last southward night mover was American Tree Sparrow, its flight call picked up three times in the wee hours of the 9th. The first-ever December (or fall, for that matter) Long-tailed Duck asked who I was, faintly, on the night of the 3rd, and here and there unidentifiable wing whistles signaled the presence of local or migrant waterfowl, which don’t let frigid nights stop them. Otherwise, the nocturnal sounds seemed mostly like late- and early-flying locals: an American Robin at 9:47 PM on the 8th; a couple White-throated Sparrows; a lone Canada Goose at 8:42 PM on the 2nd.

Thaw

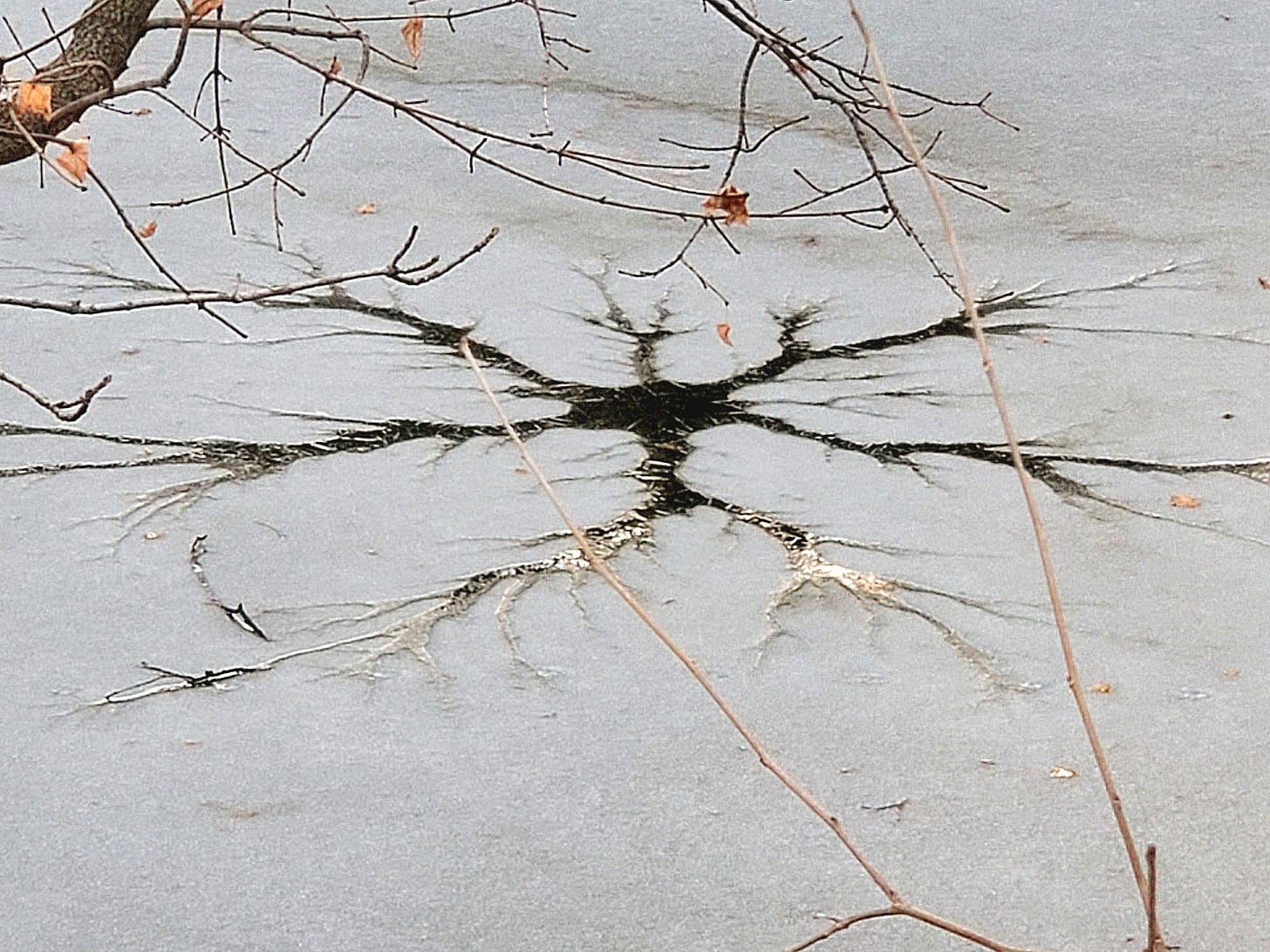

December 17 brings brief warmth, with temperatures reaching to 50. This month, I’ve been checking the pond when I can, but nothing other than a few Mallards has shown up. Mostly, it’s been either slush or frozen solid, but it’s an excuse to get some exercise, anyway. On the 17th, I park below the tracks around four, expecting the same shirt-sleeve weather (Tyrone-style) as in town. Instead, I am greeted with a blast of frigid air out of the Hollow, and nearly slip on a frozen patch. I skate east, and after only a 100 feet, I feel warm air again, and the surface changes back to slush.

As usual, all is silent until 4:30, when the first of the last starts up: a Winter Wren, clacking off by the river somewhere. Golden-crowned Kinglets buzz around the tops of the willows, and out of nowhere, a pair of Common Grackles—first-ever for December—fly over, calling, from Sinking to Logan. Just after that, a Hairy Woodpecker calls loudly from up on Laurel Ridge.

Returning across the frozen patch is like crossing by an open freezer door. I emerge on the western, Tyrone side, back into relative warmth and slush again. Down in the privet jungle, the White-throated Sparrows and Northern Cardinals get in their last, quiet, wispy words, and a Downy Woodpecker plummets up, over, and down to its final resting place for the night on the other side of the tracks. All is still after that, for a few moments, until the buzzing of a pair of kinglets, 4:55 PM, which lasts less than 30 seconds as they, too, settle in. And then, in the warm winter night, a few dark shapes flit across the tracks—cardinals, perhaps.

Holy diver

The Saturday solstice creeps closer, and with it the Christmas Bird Count, with another wave of cold threatening to descend. Count Week begins on Wednesday, and on Thursday, I am able to scout the tracks from town down to the pond and back, to see what the unsettled weather might have done to shuffle the regional avifauna around, as happens frequently in the winter here.

The first cardinal begins to tick at 7:07 AM, then white-throats whispering, and finally, duetting Carolina Wrens, singing like it’s high summer. At long last, the first Bald Eagle of the month (not that I’ve been out much), an immature, does a loop through the Gap, and then the first Belted Kingfisher of December, silent and looking for all the world like an oversized starling, jets over from river to river somewhere, ignoring the mostly frozen railroad pond. On the walk back, close the interstate overpass, a few other local residents are feeding quietly, and I step over to the edge of the riverbank to see if I can pish out whatever is twittering in the heavy brush. Slightly downstream, against the far bank, what looks like a bunch of white plastic garbage has been caught between some branches and appears to be gyrating. Due diligence: I glass it, just in case.

What to my wondering eyes does appear is a winter-plumage Horned Grebe, an altogether extraordinary ordinary bird, nothing too outlandish for still water, but a rarity for Plummer’s Hollow in the true sense of the word. It’s been over 45 years since the last and only records of this species—downed individuals in the river during the Day of the Ducks fallout in April 1979, and a headless victim a couple days later in the field. Only one other grebe, a Pied-billed, has been seen since then—also in the river. This one seems to be in good shape, swimming and diving in a glassy stretch of river. Like the Double-crested Cormorant last December, this sighting is completely by happenstance, as I don’t have the habitat of scanning every bit of river every time I walk the tracks (nothing is there 99% of the time). It’s #202 for the year.

Now all we need is for it to stick around until Saturday.

Keeping watch in the fields (Nosotros, Los Culpables)

It’s important to manage expectations when you’re pretty much certain there aren’t close to 81 species in the count circle. With La Niña Blanca chasing everything south, there hasn’t been enough warm weather this year to keep around the kind of diversity that gave our count all-time high numbers last year. The nemesis bird is still the Ruffed Grouse, pretty much the only circle-certain species we DIDN’T get last year; it hasn’t been seen during the count since 2016. We’ve got better geographical coverage this year than last, at least, and wind in the forecast, and wind means raptors.

Dawn starts for me on the balcony at 27 degrees with a 6:50 AM American Tree Sparrow flyover, and also before seven, suspiciously early, a Song Sparrow calls and a Common Raven somewhere begins to hoot. A few Mallards go over, still in the semi-darkness, and the Rock Pigeons are up and out by 7:16. Blue skies and a growing, blustery wind, and the local Cooper’s Hawk is overhead and circling as American Goldfinches bounce past. And then the reason for the early risers: that gray sheet to the north, and another to the south, converge over town in a whiteout, and the blue skies are annihilated. The squall lasts around 15 minutes, but before it’s over the starlings, House Finches, and House Sparrows are ignoring it and going about their very busy business. An adult Bald Eagle flies through a lingering flurry, over against the mountain, unfazed.

At two minutes until 8 the first American Robin goes over, and then what ends up being the only Common Merganser for the count, a male, zooms up and over the point of Sapsucker Ridge. My plan is to hang out on the balcony until 8:30, then walk the tracks with Paola to try and snag the grebe again, then go back to the balcony for a few hours to see if I can get a Golden Eagle. They’ve been late again this year, and strong flights to the north this week led to a prediction of multiples over the count circle today. We’ve only ever had singles, very occasionally, for the CBC, so it’s worth tedious hours of staring into otherwise blank skies.

Except at 8:18 AM the first Golden Eagle soars across the Gap in front of me, and I assume it heads on down Sapsucker Ridge south. I turn around and it, or another, is crossing the Gap again. I only count one (two or three more come later). Paola and I head into the frozen tundra, the temperature dropping and the howling wind numbing our gums, teeth, and brains. After a minimal amount of effort, we turn up the Horned Grebe again, which is the first record of the species for our count since 1977, and the second report ever. Not much else dares show its face, and as we are heading back, we come across brother Steve, who has logged the count’s only Eastern Towhees in their regular spots along the edge of First Field. We agree to meet up in town in the afternoon to cover some local territory that has been missed in recent years. In the meantime, Mom is taking care of the Red-headed Woodpeckers that have been spending the winter at the Far Field (she ends up getting one of the two today) and handling the feeders.

At 9:34, word comes from the team that is doing a first-ever count up in the wilds of Brush Mountain on State Gamelands 166, a multi-thousand-acre track of forest at the center of the circle. The nemesis bird is no more! Justin comments that “Dave got [the Ruffed Grouse] playing super nature tracker,” referring to brother Dave, who went up with two others on this special mission.

Meanwhile, word trickles in from some of the other teams who are on our Culp CBC social media group: Canoe Creek is mostly frozen over and waterfowl are nearly absent, as expected. Sinking Valley is turning up Horned Larks, Brown-headed Cowbird, and Northern Harriers. I’m having no luck seeing a Merlin, which I was hoping would still be around the Tyrone skies. Bald Eagle reports are coming in here and there, and as the morning wraps up I start to check on potential misses. Red-shouldered Hawk, which showed up in record numbers in a nearby count, is absent, but American Pipits seem to be about, and Eric’s Lower Lower team gets a Turkey Vulture and Hooded Mergansers. John Carter reports Yellow-rumped Warbler, missed on a nearby count, and a few other unusuals also pop up on the eBird reports now starting to filter in. By 2 PM, we have around 60 species for the count.

Steve, Paola, and I head out to some overlooked Tyrone spots. In the unlikely village of Northwood, straddling the interstate, clutching the side of Bald Eagle Mountain, we find crowds of birds mobbing crowds of feeders, with the day’s only Red-winged Blackbird among them. Cemetery Hill, sunny and melted, faces the Gap, and among the flocks of common smaller birds we find Wild Turkey tracks. A trio of adult Bald Eagles transits their eponymous mountain. We peek into the other forgotten corners, and finally wrap it up close to five over by the ghost of a covered bridge in Grazierville, as the last Winter Wren calls.

On our social media group, Sinking Valley announces the Short-eared Owl as the one that got away, but their consolation prize is a Rough-legged Hawk, a species not seen on the count since 2009. With the addition of Tundra Swans that went over Plummer’s Hollow while we were all gathered for the count supper, the provisional list stands at 69 species, about where the other counts in the area ended up last weekend—not in the stratosphere, but still quite impressive, given the weather. With a few lists outstanding, it is still possible for us to get 70 species, though probably not those annoyingly undetected ones: Red-shouldered Hawk, Merlin, Barred Owl, Common Grackle, Snow Bunting, all lurking either in the circle or nearby.

The other girl

That meteorological travesti, La Niña, is promising a warm-up in 2025, if there is one. I’m praying, instead, for our very own Saint Death to stick around the rest of the winter; the cold, at least, is peaceful. Hasta entonces.