Final numbers are in, and July 2024 in Plummer’s Hollow edged out July 2023 by one species, thanks to some unexpected, last-minute additions since my last update on the 24th. Indeed, the final week of July was one of the most intriguing of the year so far, reinforcing my fascination with this often overlooked and underappreciated month (among birders, in any case).

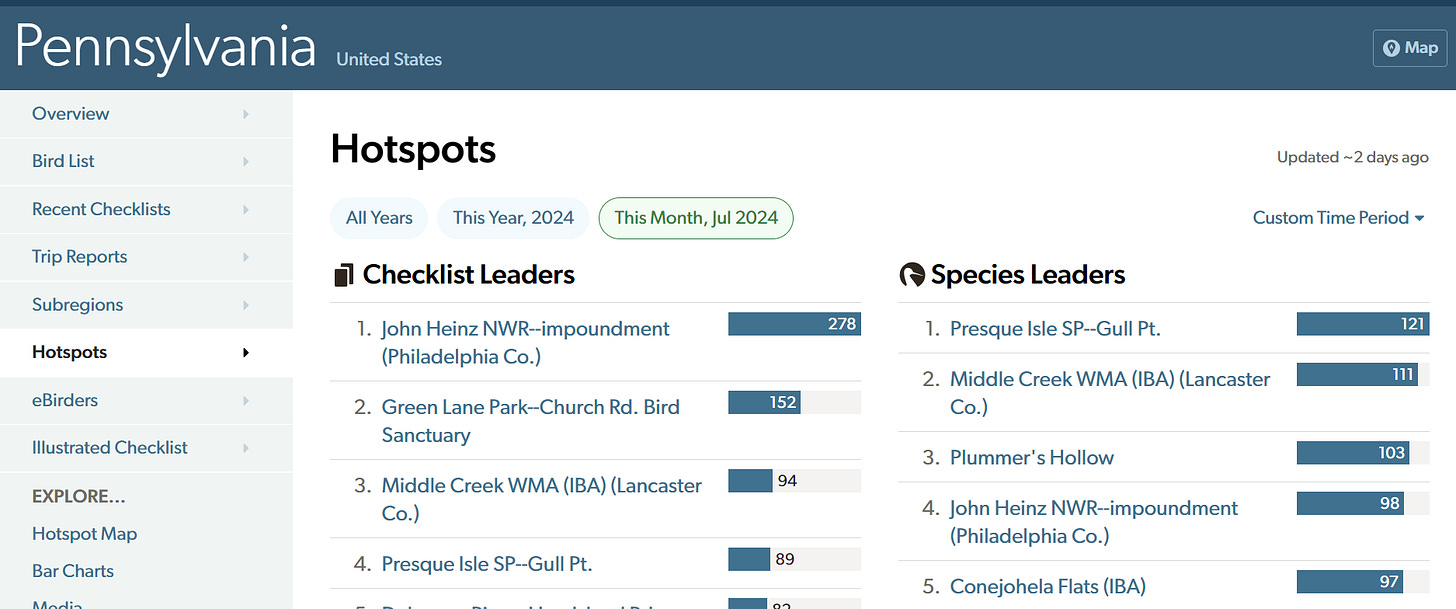

By the numbers, last year’s (Big Year) July total, combined with this year, saw 120 species detected in the hotspot for the month, out of an all-time July total of 135. Of these 135, nine were first detected this July, including some of the last week’s sightings and recordings, and other oddities like the Peregrine Falcon.

What’s more, with Plummer’s Hollow’s year list now at 193, we are five species ahead of last year at this time. It is now looking quite likely that we’ll pass 200 species for the second year in a row (with less overall effort, more targeted). Whether we’ll surpass last year’s 203 is anyone’s guess, as there is only one species left (Connecticut Warbler) that I am certain will be recorded. NFCs such as Black-bellied Plover, American Golden-Plover, and Dickcissel are certainly likely, and Blue-winged and Golden-winged warblers, or at least the former, should make appearances by late August. Beyond that, I would say a few of the missing duck species would be nice (Northern Shoveler, Blue-winged Teal, Hooded Merganser), but if you’ve followed this blog for any time, you’ll know how unpredictable waterfowl sightings are here (though scroll down for some inspiration…).

What else? I’m not going to throw in the towel on the Olive-sided Flycatcher just yet; this year’s extended Yellow-breasted Chat visit gave me some hope that even the least-frequent migrant passerines still make appearances. I will definitely make the effort to pick up a Northern Saw-whet Owl in the Hollow at the end of October, and I’ll scan the skies again for a glimpse of a Bonaparte’s Gull. Maybe a Snow Goose? An Evening Grosbeak? A Snow Bunting or a Lapland Longspur? Most likely, beyond the above-mentioned, one or two quite unexpected species will pop by, new for the hotspot or absent in the past few years.

A Rare Duck Makes an Appearance

In the midst of a string of muggy, subtropical days, I relished the dry high that came in around the 26th. That morning’s crystal-clear air and low-50s temperatures brought quite the parade of surprises past the balcony.

As usual, I heard the quacking before I saw the ducks. Above the confluence, the water surfaces of the Little Juniata River and Bald Eagle Creek are invisible to me, so duck noises are often the hint that Mallards, or rarely, something else, are about to swim into my field of vision, before floating on downstream, out of sight again.

Not unsurprisingly, the quacks were mostly from Mallards: 22, to be exact, more than I had seen since the end of January. In among them, completely unexpectedly, was a male American Black Duck, which I have to admit I wasn’t expecting for another four months. As it swam and interacted with the Mallards, I confirmed the ID and then ran inside to get the long lens. As usually happens, by the time I was able to focus, he was gone.

Other than our local breeding waterfowl, I don’t pay much attention to or expect to see dispersing individuals of rare species in high summer. There is no way to know where this particular black duck came from, but I discovered that they have bred successfully this year at Yellow Creek State Park some 30 miles to the west.

While certainly the first of its kind for the hotspot in July, it is seen every once in a while in Blair County during summer. For example, in 2022 one was seen and photographed at a farm pond not far from Plummer’s Hollow on July 18, in the company of Mallards. The first-ever black duck in Plummer’s Hollow was one that my older brother Steve saw overhead on March 8, 1987, and the only other record prior to 2020 was an unusual sighting that my dad, Bruce Bonta, had from the stream below the field on April 26, 2006. With regular monitoring of the railroad pond starting in 2020, I began to record a single or a pair there, mixed in with a large Mallard flock, every year between the 1st of November and very early January.

Quiddyquit for a Second Year, and the Missing Tringa

The three-note call of an Upland Sandpiper was picked up about half an hour before midnight on July 20th. It beat last year’s by almost three weeks, and also got recorded before the katydid curtain descended. Click to read last year’s account.

Lesser Yellowlegs (Tringa flavipes) made its first 2024 appearance at 5:06 AM on July 23rd with the typical peer flight call. This relatively common night flyover (by Appalachian mountaintop standards) does not seem to follow a schedule: its previous recorded dates were 5/13, 7/17, and 9/2 for 2022, and 4/29 for 2023.

The Greater Yellowlegs (Tringa melanoleuca) follows a somewhat more predictable schedule, its wild and wonderful 4-note flight call ringing out in late April and early May, once (this year) in mid-July, and again as one of the last southbound NFC migrants during the first two weeks of November. Even more frequent is the Solitary Sandpiper (Tringa solitaria), the only sandpiper species other than the Spotted that can be seen as well as heard in the hotspot, usually at the railroad pond or along the river. Solitaries show up from mid-April to mid-May, and again in July (NFCs only), with no records after July 28th.

The fourth of this genus, the Willet (Tringa semipalmata), is by far the rarest, with so far only one report, from April 30th of this year.

Invasion of the Fish Crows

Around 6:20 AM on that prodigious morning of July 26, Fish Crows reappeared after a nearly two-weeks’ absence. This time, instead of the distant uh-oh from a local pair that I heard occasionally during breeding season, this was several family’s worth of crow. As usual with this species, I heard them before I saw them, straggling in from the east in worried-sounding singles and pairs, alighting on the trees over Bald Eagle Creek, then the posts and wires, then on over the downtown rooftops. Close to a dozen American Crows showed up as well, and I think the robins became quite preoccupied with these nest robbers. Before and while the corvid invasion was happening, two robins perched near the balcony, emitting their high-pitched alarm calls.

Eventually, two Common Ravens swooped silently down from Sapsucker Ridge. After no more than 20 minutes, the crows and ravens all turned around and straggled out the way they came, down the greenway of the Little Juniata, croaks, cackles, caws, aws, and uh-ohs dying away in the distance. Later, I checked the numbers, and the 16 Fish Crows was a new high count for the hotspot.

Balcony Cameos

Perhaps all this excitement was what lured in one of the local Cooper’s Hawks for only the third appearance of the summer, and the first time in months I saw one fly past the balcony (other sightings tend to be in late-afternoon thermals).

Two other scarce July residents were a Green Heron and a Belted Kingfisher, both a couple days later.

Cliff Swallows on the Wire

Cliffs Swallows, like all other swallows except Purple Martins, have been scarce this year in the hotspot. While a pair or two of Cliffs usually nests under bridges above our section of the river, this year it seems that none did so successfully. They’re most reliable during “fall” migration, during which they appear in single-species flocks, or mixed with other swallows, low over First Field, often perching on the wires nearest the barn.

This year did not disappoint. On the evening of July 29th, Dave texted me about a large and confusing congregation of swallows he and Mom were watching, which turned out to be about 40 Cliffs and some ten Barns. In other years, we’ve observed flocks of up to 100 at a time. In 2020, this event (also a count of 40) first occurred on July 30th, while other years they tend to concentrate in late August, after which they disappear entirely from the skies (of all the swallows, only Barns have been recorded here as late as September — once, a pair, on Sept 3, 2023). The all-time high number was on August 27, 2020, with highly-rounded estimates of 100 each for Cliffs, Trees, and Northern Rough-winged Swallows. My comment on eBird for a morning checklist was “Probably undercount. Sky over the ridge and fields was filled in every direction w CLSW, TRSW, NRWS.”

The Most Precious Plummer’s Hollow Family

After an absence of four years, Ruffed Grouse chicks provided solid evidence of breeding in the hotspot. On the evening of the 28th, at 6:19 PM, the following exchange took place:

Eric Oliver: Just flushed two yes TWO grouse. Ovenbird [Trail] at Laurel Ridge.

…Make that 3

…Now 4

Me: Whoa, where exactly? How many grouse?

Eric: 4. One mom and 3 good sized poults.

Eric: I flushed first two then wegiel [dog] got birdy so I let him work the huckleberry some and he put up two more.

Me: That spot is about .75mi or 1 mi SW of where I flushed a pair in courtship season [March].

Dave: That’s such great new about the grouse…I called Mom to tell her and she was pretty excited too.

Grouse tend to stay in the thickest brush, and move back and forth from our property to surrounding lands. In recent times, there have been between five and ten reports per year in the hotspot, mostly in winter and spring, of this nearly-extirpated species (West Nile Virus + ?). On May 30th 2020, a mother had been seen with eight chicks at the Far Field. Prior to that, the species had declined steeply, and no other evidence of breeding is known to me after 2007. To put this in perspective, Ruffed Grouse were ubiquitous on the mountain in the 1970s and 1980s, and seeing a mother with young was about as unusual as seeing a White-tailed doe with fawns back then.

Postlude: August Doldrums

As predicted, the katydid curtain descended at the end of the month (with cricket hums and drones to add insult to injury), and in addition, we were mugged by another stretch of hot and stagnant days and nights, punctuated by a series of violent storms that ended the drought. On the last day of July, I was sitting on the balcony to welcome one such post-storm dawn, thinking (obsessing, actually) that the conditions were just right for a wandering Great Egret, a species that had thus far eluded me in 2024.

Sure enough, within minutes of that thought, one glided in from the north at 6:10 AM, followed not long after by an Osprey that had been hanging around. (I later detected an egret from the night before on the NFCs.) The following morning, the first of August, I saw perhaps the same egret as the day prior glide overhead as I was walking along the tracks not long after 6 AM.

And then the long quiet of the morning birds that characterizes the last three weeks before fall migration ramps up. Though the unexpected appearances of molt-migrants and other wanderers has ceased, the weather has been anything but quiet. The river flooded from a frontal system immediately followed by the remnants of Tropical Storm Debby during the first full week of August.

After the storms cleared out, we finally had a good summer raptor count. These only happen this time of year with late-day thermals, and on August 9th, the weather was just right to send a Black Vulture along Bald Eagle Mountain, a Broad-winged Hawk over the balcony three times, and a Cooper’s Hawk hovering beyond the towers. With a Sharp-shinned Hawk detected by Dave a few days ago up in the spruce grove, that leaves only the Red-shouldered Hawk missing from the summer resident raptor tally this year.

The main species of note so far has been an Eastern Kingbird, the second record of the year and the first good view since spring 2023. On August 11th not long before 8 AM, one landed on a snag not far from the balcony—an unexpected, latest-ever record of a species that we have never recorded before in southbound migration. It perched for a full two minutes, long enough for me to snag a few photos.

That evening, I watched mom and dad Barn Swallow still tolerating the begging of six young that congregate every night on a wire over the parking lot. As the parents came and went from the wires, they tussled repeatedly with an Eastern Phoebe hanging out in a nearby tree.

House Finches and Chipping Sparrows, both up in numbers from this year relative to last year, also screamed and yelled at their parents to keep stuffing them with food. Meanwhile, Cedar Waxwings and American Goldfinches seem to have raised some young, so I can safely say that the breeding season is winding down.

Last but not least, the Brown Thrasher finally and officially became a year-round species, with one seen on August 6th plugging a 50+-year thrasherless void during which I had always assumed the species deserted the mountain after breeding season. This year, several juveniles were around in late July and early August, and quite easy to detect along the edge of the field.