As I commented at the beginning of this month, the spring migration wrapped up much earlier in 2024 than in 2023, to judge by the bare trickle of night flight calls in early June. Night skies over Plummer’s Hollow were silent the second half of June and into early July, after which NFC recordings stopped due to an electrical project, resuming on the night of July 12-13.

The highlight that night was a long series of Greater Yellowlegs at 3:58 AM, an expected southward migrant, but one we’ve never recorded in high summer before. Other July shorebirds included a couple of Solitary Sandpipers on the 15th and the 18th, and various unidentified things.

Marsh Bird Mystery

At 11:16 PM on the 14th of July, a Sora called once in flight. This is the fifth record for the mountain so far in 2024, quite a feat considering that last year, the rail was recorded only once (the first-ever record for Plummer’s Hollow), on April 14. In 2024, calls were picked up on April 11 and 28, on May 10, and on June 3. Even the early June call was plausibly a late migrant, but mid-July?

Knowing next to nothing about Sora migration patterns, I turned to Birds of the World. Not much help: “Timing and Routes of Migration - Little known. Because species is reclusive and difficult to observe, migrants are not easily detected. Vocalizations are useful in locating migrants in spring; in other seasons, less vocal and so more difficult to detect.”

Finding no mention of Sora summer movements in BOTW, I turned to eBird. A June 21, 2024 checklist from Lycoming County at a site some 60 miles northeast of here documented Sora with young, and there are scattered other 2024 records of the species from wetlands throughout the central part of Pennsylvania. Back at BOTW, I learned that young may start dispersing by six weeks after hatching, and that drying up of wetlands may also result in Soras leaving breeding grounds.

Sora are recorded now and then throughout the summer from wetlands much closer than 60 miles away—indeed, I would be surprised if the species didn’t breed at one of the numerous under-surveyed and private wetlands in nearby valleys. While the origin and destination of this particular individual will remain forever a mystery, it’s nice to add another data point to such a poorly-understood dynamic.

Speaking of poorly understood and overlooked, July 4th delivered a night heron, a bird I have always wanted to see in the hotspot. I’ve gone purposely to the Plummer’s Hollow bridge on several occasions in May and June in hopes of glimpsing one; they’re quite rare around here and don’t breed anywhere nearby, but I’ve seen them a few times in the next county to the north, Centre. At 5:08 AM, a juvenile night heron flew upriver, not far from the balcony, but it was still too dark to ID to species, and it made no sound.

As with the Sora, there has been an uptick in night herons in the hotspot in 2024, but in this case, from a baseline of zero. The first-ever was a Black-crowned on April 19th at 2:20 AM, and the second was another of the same species at 10:18 PM on May 20. I fully expect a Yellow-crowned at some point—both species wander through in migration and, on July 4th, what I assume was some other type of population dynamic.

Night Migrants, Molting and Otherwise

Strange and cryptic movements are one of the main fascinations I have with July. The terms “molt-migration'“ and “post-breeding dispersal” seem to refer to a wide range of behaviors that in some species, like the Sora and night herons, result in nocturnal and crepuscular movements over non-breeding habitat (like Brush Mountain).

One notable sub-category is passerines of grassy and edge habitats that are displaced through mowing, burning, or other high-summer habitat modifications. Indigo Buntings, Chipping Sparrows, Common Yellowthroats, Swamp Sparrows, and even a Savannah Sparrow on July 11—it’s impossible to know exactly what they’re up to, but their flight calls reveal them regularly at night over the ridgetops, and sometimes at dawn as well, zipping above the balcony.

The night of the 12th-13th saw a fair amount of high-pitched calls that might have been Grasshopper Sparrows, a species that isn’t migrating southward yet and doesn’t nest in Plummer’s Hollow. At 4 AM on the following night came the first definitive seet flight call of high summer.

Molt-migration of Wood Thrushes was also underway by mid-July. The night of July 13-14 registered at least ten veets. The Veery situation is a bit more confused, as there is a persistent movement of birds on the rare, windy July nights that are a toss-up between thrushes, Rose-breasted Grosbeaks, and shorebird-like sounds. The first classic Veery night call came around July 20—molt-migrant or southward mover, or maybe both—while the first (almost certainly) southward-moving Swainson’s Thrush flew over at 2:50 on July 19.

Warblers on the Move

The southward migration may actually have kicked off around July 4th with out-of-breeding-habitat Black-and-white Warblers, Louisiana Waterthrushes, and American Redstarts—three species known to migrate long distances in July, but also to disperse locally prior to that—heard and occasionally glimpsed every morning from the balcony, mostly along the river and the creek.

When recordings started back up on the 12th, zeeps, ups, and redstart NFCs belied nocturnal warbler movement over the ridgetop, albeit quite light.

July 6th brought a singing Northern Parula and a singing Common Yellowthroat to the confluence for single dawn appearances; neither are known to be July long-distance migrants, so these were probably simply dispersing from nearby breeding grounds, as was a Black-throated Green Warbler on the 13th.

Up on the mountain, mixed flocks began to coalesce in the woods after the middle of the month, with some containing upwards of 30 species. While many or even most of these birds may be from the immediate vicinity, three definite molt-migrants candidates were Warbling Vireo, Willow Flycatcher (the year’s first, as it was missed in spring migration), and Chestnut-sided Warbler.

Warbling Vireo is an interesting case. Every balcony morning from April 23 onward, I heard its song, until the last time, on July 14th. The first extensive survey I did up on the mountain after that, the 18th, te species turned up on Bird Count Trail in a huge mixed flock. On the 21st, another was foraging high up in a black cherry at the edge of First Field, and scolded briefly.

The other two species moved in from farther away, as they do not nest within the hotspot, but likely do nest no more than a mile or two away.

Purple Martins’ Majesty

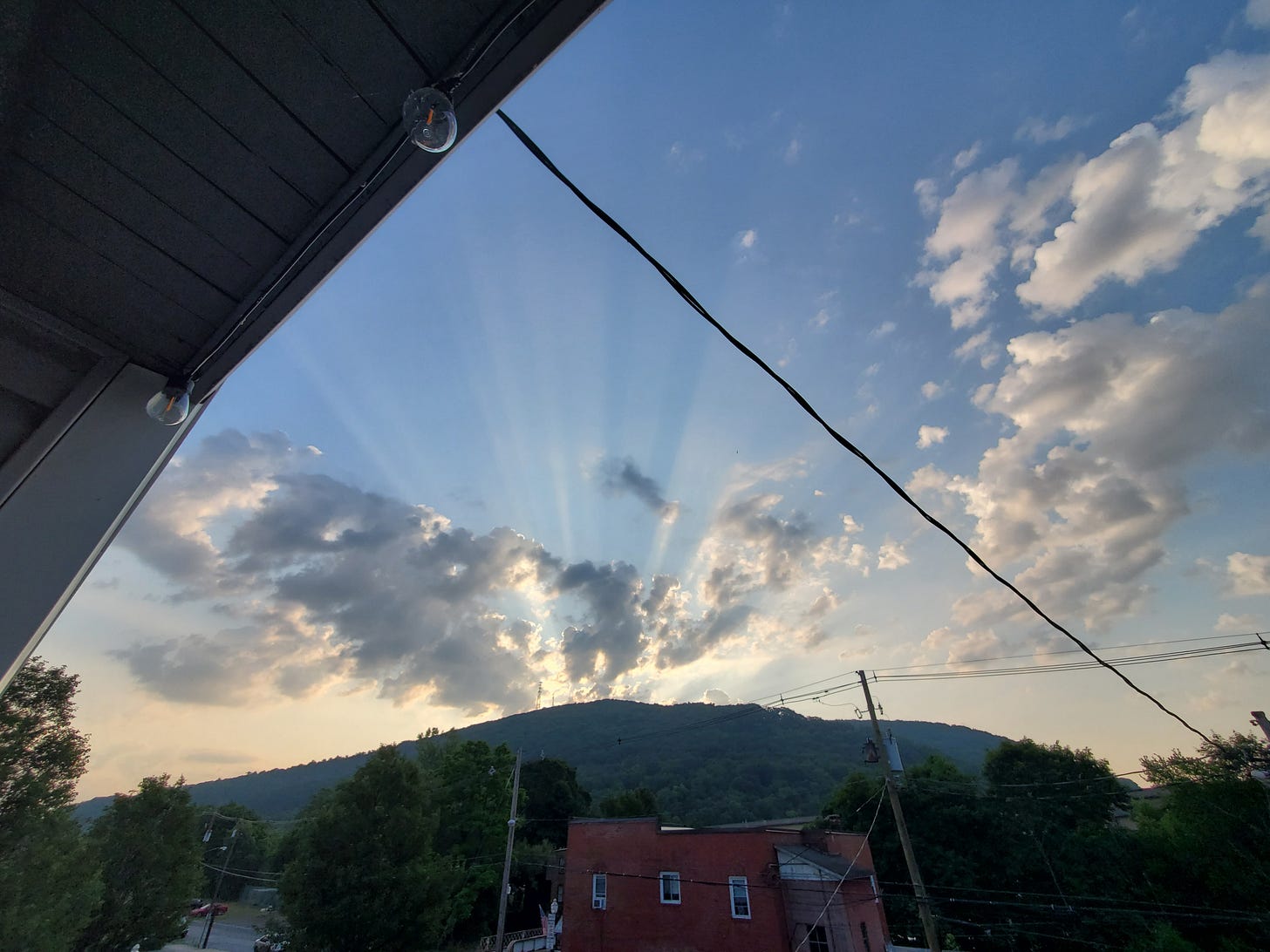

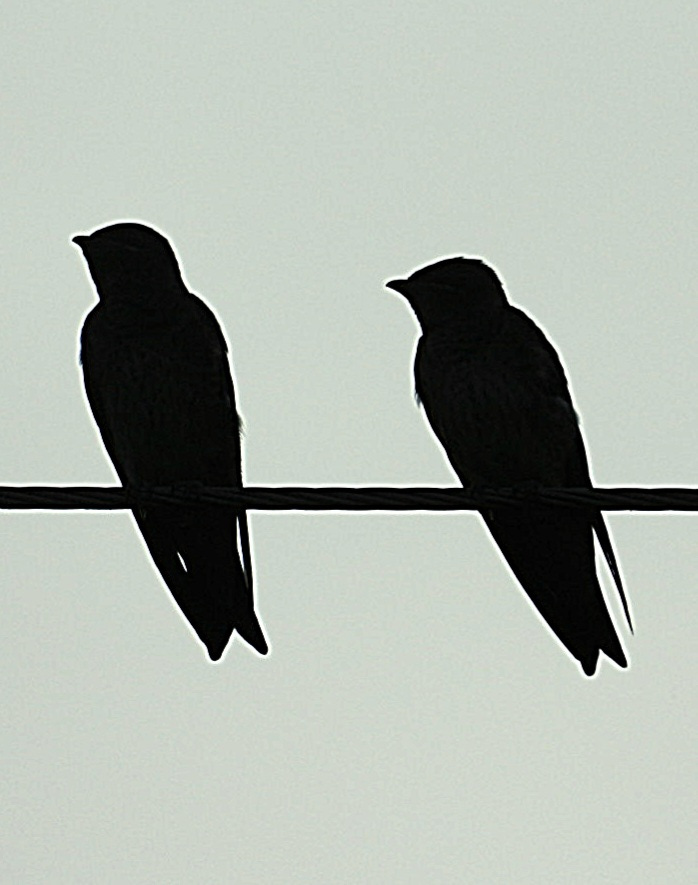

Excuse the terrible pun. Martins, one of the world’s largest and most-loved swallows, has been increasing in numbers in the area thanks to more and more martin houses that Amish farmers are erecting in nearby Sinking Valley. The species returns in April, but they aren’t seen much beyond their breeding locations until the aerial bug population swells. Toward the end of May, their churring calls can be heard in the earliest moments of dawn twilight, long before they’re visible, over the fields and ridgetops of Plummer’s Hollow. In June, they can be seen occasional crossing over the mountain or through the Gap.

In July, for the first time in living memory, they began to congregate on the wires around the barn. The majority appeared to be juveniles, and they weren’t shy. Starting around 7 AM, pairs appeared, sometimes mixed with a few Barn Swallows and Chimney Swifts, hunting over First Field. As the month progressed, more and more martins were about during the day, and they eventually began to alight on the wires closest to the barn. These may have been a post-breeding congregation from far away, or a temporary staging activity for young birds from half a mile off in Sinking Valley. The peak—18 individuals—happened around the 12th, and after that, numbers began to dwindle.

Growing Silence at Dawn

The highest dawn balcony species numbers for the entire year are in early and mid-July, spread over a couple hours of activity, from the still-deafening American Robin chorus that kicks off before 5 AM, which hasn’t let up since February—all the way until 7 AM, a quarter hour before the sun crests Bald Eagle Mountain. Peak balcony count was reached on a quiet Sunday, the 14th, with the unusually high number of 41 species.

Soaring list numbers in early July result from a combination of large quantities of successfully fledged birds moving to feeding grounds, the last couple of weeks of territorial singing for several species (except American Goldfinches, who will be at it for a lot longer), and the appearance of unusual movers, possibly molt-migrants, like Swamp Sparrow, Eastern Kingbird, Red-breasted Nuthatch, and Belted Kingfishers. After a fully two-month absence from the hotspot, three kingfishers rattled their way through on July 5th, one landed on a wire over the parking lot on the 7th, and one called from below the confluence on the 13th.

Occasional updrafts may even kick up something extraordinary, like the Peregrine Falcon on July 10th, our first-ever summer record. Not surprisingly, it was hunting pigeons high above the interstate. (Updrafts also help for detection of locally breeding raptors, which otherwise aren’t easy to detect in the muggy, still, and suffocatingly warm July weather).

Then, one by one, the breeding birds, having bred, fall silent, and species numbers drop back down into the low 20s. Chipping Sparrows stopped their daily dawn trilling after the 18th. Gray Catbirds became quieter and quieter. Then, on July 22nd, and every day thereafter, the Song Sparrow became the first singer, as the robins, though they didn’t fall silent altogether, ceased their dawn chorus.

Blame it on the chemicals of lust, which in most species have ebbed. The robins are up in the mountains in mixed-age flocks, along with others that have left town, like whole families of Baltimore Orioles. Barn and Northern Rough-winged swallows are mostly off congregating in faraway valleys, but not here: by the 24th, only a single Barn Swallow was left. Even Common Grackles and European Starlings have mostly found better places to eat and sleep and cackle than my edge of the hotspot. Both species are moving in relatively large numbers—dozens and even hundreds—at dawn and dusk—between summer roosts, mostly passing overhead, but not coming close.

Not all species are mute, however. Carolina Wrens, after their enforced code of silence during breeding, are now singing and calling and moving around in groups, in any and all habitats, so vocal that the all-time high number, achieved earlier in the year, was reached on July 20th, with 18. Song Sparrows and Northern Cardinals, two others that rarely ever stop singing, also didn’t get the memo about the end of breeding season (or perhaps they’re raising more young). House Finches, meanwhile, are singing less and calling more, and by now they’re commuting every dawn out of town in all directions. Chimney Swifts and Rock Pigeons? If anything, they’re more active now than ever.

The River

On the 23rd, the first mixed family of Common Mergansers came upriver at 6:44 AM, a tight group, flying pretty low, and none in adult male breeding plumage. Well over a dozen Mallards, mostly young, have been swimming about the confluence, and on the 21st, I glimpsed around a dozen flying in disarray down through the Gap. On the 5th, I spotted a family of Wood Ducks at the pond, scampering across the mudflat, five fuzzy ducklings among the lily pads. Another breeding success! Canada Geese, meanwhile, have been completely absent from the skies and waters.

Beyond kingfishers, a night heron, and a nearly ever-present Great Blue Heron (even late at night!), the Little Juniata River brings a trickle of nice surprises throughout the summer. Nearly every morning, one or two of the several local-area Bald Eagles cruises low through the Gap, heading east, not long before sunrise. For the first-time ever, on the 28th, I got to watch one walking about on the rocks upstream of the bridge—an adult, picking about for fish or carrion of some type, I would guess.

I think our local eagles are gradually getting tamer, but they’re not as fearless, yet, as Ospreys. This summer’s Osprey experience happened on the 20th at 6 PM. I happened to step onto the balcony just in time to watch one follow Bald Eagle Creek downstream, a few yards above the tree line, then veer left and head downriver and out of sight, calling loudly. I can’t recall seeing them this close in the summer—usually, they’re soaring around the towers and even perching there. Unlike Bald Eagles, they are fearless enough, at least in migration, to perch close to the apartment on power poles, sometime eviscerating a fishy snack in complete disdain of passing vehicles and people.

As the Trees Begin To Drip…

By the 18th, the suffocating heat that started around mid-June began to abate, at least temporarily. We saw day after day in the 90s, and sweaty dawns above 70, a feat we only reached once or twice last summer. To my great relief, we weren’t smothered by the smoke from Canadian forest fires this year, but that discomfort was swapped for bugs, legion in the Hollow.

The silver lining of bugs, when you combine them with wild fruit crops and acres of dense cover, a multi-tiered canopy, and a rich ground layer, is an absolute bonanza for birds. This becomes quite noticeable in the second half of July, particularly in the tangled woods between Dogwood Knoll and the Far Field, on the high-concentration, east-facing slope of Sapsucker Ridge, particularly in areas of grape vines and black cherry. While a few species—goldfinches, Cedar Waxwings, and a few second- and even third-nesters—are still trying to breed, most others are combining into larger and more complex flocks, taking on the habits of the tropical forests many will soon return to.

It’s a fascinating scene. A little pishing can bring in a family of Scarlet Tanagers, multiple hummingbirds, Red-eyed Vireos (always present, always cool to watch), five or six Black-and-white Warblers at a time, and these bring others, until nuthatches are running up and down trunks, Eastern Wood-Pewees are scrapping with redstarts and downies, towhees and cardinals and grosbeaks and endless others are flitting about, singing, begging, scolding.

One by one, the eBird tally lights up in yellow, as high-number filters are tripped on these July circuit hikes. The most sublime all-time high-numbers record of the year was the Wood Thrush, with 54 heard singing on the 20th, mostly in the first hour of the morning in the deep hollow. Given the NFC evidence, I have to wonder if the Hollow’s numbers—which are presumably much higher than this, as they don’t include silent, young birds—are being augmented by molt-migrants? It’s hard to describe the overwhelming dominance of Wood Thrush song in the lower Hollow between 5:30 and 6:30 AM, as most other breeding-season early-morning singers have already fallen silent for the year. I would like to think the Hollow is a magnet for such species immediately post-breeding, and not just later, during long-distance migration (in a month, when the woods are seething).

Katydids Close In

All good things NFC-related, inevitably, come to an end. The end, to be clear, is katydids. Their shushing calls start to clutter the spectrum by mid-month, first as slight interruptions, then as longer annoyances, and finally, by August, as a solid band of blackness that obliterates all but the final minutes before dawn. The only NFCs to make it through the katydid curtain are easily-recognizable, common ones that show up, all blurry, in the occasional quieter periods. The NFC collector’s only ally in this struggle is time and cold. An infrequent chilly night will shut the buggers up, which could mean a rarity like last year’s Upland Sandpiper. Otherwise, it’s six weeks of beautiful noise.