This kind of dawn—

—brings the cloyingly sour-sweet stench of the sewage treatment plant through the Gap and into my nostrils. East breeze—the worst kind. After weeks of drought and elevated fire risk, November 10 is supposed to usher in a spell of rain, and just in time, too, as mountainsides are beginning to blaze in the Ridge-and-Valley. The wind is wrong; it should be out of the northwest or at least west this time of year, but here we are. The southern birds are long gone, but the South is still rising.

It’s been quite some time since I did a full balcony sit, so I’m not quite sure what to expect, but hopefully something more interesting than the boisterous congregation of European Starlings on the tallest trees to left and right, greeting the sun’s first rays that now issue from halfway between Sunnyside and Shadyside.

Because of a Mexican interlude, the Plummer’s Hollow list is still missing some common birds for November, including good ol’ pigeons. We’ll no doubt tick those off, and who knows what else? At 6:20 AM, an American Robin exclaims, and a bit later, a couple indefatigable Carolina Wrens and the other locals. Sunday stillness sets in again at 6:30, until the distant twitter of American Goldfinches 15 minutes later is followed by a burst of aerial activity.

Close to seven, a group of a dozen or so Rock Pigeons, the first of the day, gyrates low over the rooftops—odd behavior, as they should have been heading over the mountain by now. Immediately, a slightly larger bird hurtles into the flock, and feathers fly. Somehow, the pigeons escape skyward, and the Peregrine Falcon, which must have been perched and waiting on one of Tyrone’s skyscrapers, flaps away from town to do a lap around Bald Eagle Mountain. It’s another quarter-hour before the pigeons send out another vanguard, but by that the Peregrine is doing loops far up and off and ignores the rest of their commute.

In the interlude, the rest of the birds have woken up and headed out, including three nice flocks of blackbirds, with identifiable Red-winged Blackbirds and Brown-headed Cowbirds; probably a Rusty of two in the mix (this is their time), but no way to tell in the few seconds they pass overhead from up creek to downriver. For a minute or so I can’t be sure if a Common Grackle was also in there, but as if to clarify, a single male flies clucking back into sight, and then goes back south again. Redwings and cowbirds might stay around throughout the winter, but it will be a first if a grackle shows up between the end of this month and the New Year. Grackles reappeared in the hotspot on October 23rd after a nearly 3-month drought, and on October 26th, a flock of 150 moved through the trees on Sapsucker Ridge.

At 7:18 AM, ten minutes before the sun hits the balcony, a Cooper’s Hawk dives close over my head and lands on the nearest tree by the river, facing away but glancing back at me, tail shivering. In seconds, it is gone.

The Final Hours of the Drought?

After Paola returns from the graveyard shift, I head up to the mountain for the first thorough hike in over a month. Sickness, back injury, and the Yucatan have made it difficult to find the time, though I have managed to harvest all the NFCs and make a few circuits of the field now and then. Mom has been avidly observing a Red-headed Woodpecker that has taken up residence at the Far Field: the best looks she’s ever had of a species I came to love in Mississippi. She also goes up every day to Dad’s resting place inside the spruce grove, feeding the growing crowd of birds that come to drink from a concave stone Dave placed alongside Dad’s grave marker.

I search the grove in vain for a Red-breasted Nuthatch; the last one I logged was October 26. But otherwise, the winter birds are mostly here, or at least passing through. Purple Finches are hanging about, and Mom watched two males at the feeder already; their pings are picked up most early mornings on the antenna. Winter Wrens are all about, particularly along the tracks; up top, I watch one bounce about the top of a shrub at the Far Field, scratching its ear repeatedly. The other day I had the first American Tree Sparrow within the seething mass of sparrows flocking through the goldenrod, stalks all dead now but still prime real estate.

The scarcer movers are also about, though they don’t have anywhere to put down in the hotspot: American Pipits have been going over at night and in the early dawn hours since Oct 25, and Horned Larks since Nov 7. The other day, I left my phone on top of the car by the garage for a bit, and Merlin ID’ed a Snow Bunting, but the recording showed no sign, so #199 will have to wait.

The rain is slow to arrive this morning, but the smell of smoke from a wildfire that broke out a couple days ago near Canoe Creek, to the west, has faded. As the first drops finally arrive (eventually leading to a full inch of precip), I find ten Pine Siskins, oblivious to my presence, gorgeous on black birch catkins along Ten Springs Trail. Eventually, something alerts them to my presence and they flurry off, even more frenetically than the goldfinches that are still about the mountain in scores.

A New State Record

Writing this just now, I realized that Sunday’s Fox Sparrow total—77—is the highest number recorded in Pennsylvania (for eBird, anyway), surpassing the 75 reported along a 20-mile stretch of road over the course of an hour in Dauphin County on March 17, 2007. While it took me more time (about three hours), this particular Plummer’s Hollow stopover population is far more condensed than the 2007 one, with a couple dozen together in each of two preferred spots (consistent season to season) across a mere half-mile of Sapsucker Ridge thickets and field edge habitat, a band of vegetation no more than 200 yards wide, mixed in with White-throated Sparrows and Dark-eyed Juncos, with other, smaller groups elsewhere along the same stretch. I have little doubt that several dozen more escaped detection, as I did not have time to access the thickest and steepest parts of the ridge before the rain set in. Nor do I necessarily think that November 10 was peak Fox Sparrow for 2024, as the numbers appear to have been quite high this entire month. I do find it intriguing that Sapsucker Ridge’s invasive-filled, southeast-facing upper slope hosts the consistently largest Eastern Towhee and Fox Sparrow populations in the state; I welcome any speculation, wild or otherwise, as to why.

The Waterfowl that Weren’t

Even in the best of times, Plummer’s Hollow’s fall waterfowl migration is marginal, and this is the worst of times. By this time last year (and as early as Oct 20), the railroad pond already had 30 to 40 migrant Mallards on it; this year, the most I’ve turned up is a pair in its disjunct puddles connected by muskrat trails. Thankfully, an American Black Duck appeared over the summer this year; a pair of 2023’s species #200 was with that group of Mallards on Nov 1 last year.

Thanks to NFCs, November has seen a few Wood Ducks screech by, a single Tundra Swan, and some Green-winged Teals, but that’s it. We’ll see what the forecasted change in weather brings.

The Eagles (Aren’t) Coming!

While I’m at it, I should point out that the Golden Eagle migration has largely been a bust so far this year, thanks to the dearth of northerlies. I was quite excited to watch the first one of the season coast overhead at the top of First Field on October 26th, but even the dedicated watchers in the area haven’t seen many more than that since then. As I’ve not had much opportunity to scan the skies, I’ve missed the few Northern Harriers and most other migrant raptors this fall, though I keep getting better and better views of the local Bald Eagles as a consolation prize. On that same October 26 morning, I watched five adult Balds flying around in circles just over the ridge, chattering at each other in some unintelligible slang. This went on for a good ten minutes, until two juveniles showed up and they moved down the ridge and out of sight.

Warblers from Here to the Yucatan

That same day, I pished in a late Nashville Warbler, and two days later, the last Palm Warbler went over at a few minutes to midnight, leaving only Yellow-rumped Warblers which, as of the second week of November, also now seem to be gone.

Appropriately, it was peak Palm Warbler when I arrived for a week of R&R in Ekab, along the sandy barrier island of Cancun east of the Nichupte Lagoon. Individuals were everywhere on the hotel grounds and in the grassy parks and waste spaces, wagging their tails like all get out.

Right next door, the newish Cancun Maya Museum and San Miguelito archaeological site, the ruins of a community that lasted until a decade or two after Conquest in the early 1500s, was engulfed by dense vegetation, hiding numerous migrant warblers fresh from Pennsylvania or other points north: American Redstarts, Northern Waterthrushes, Yellow Warblers, Magnolia Warblers, and many more. Among them was the tame and very curious endemic Black Catbird (Dzibaban in Yucatec Maya), one of around 20 species found almost exclusively in the Yucatan Peninsula. The first one I saw (lifer!) was accompanied by a Gray Catbird (Ch’iich’ miis).

From the museum’s balcony, highly enthusiastic Argentinian tourists pointed out a Summer Tanager (X jeret) feeding on a cecropia.

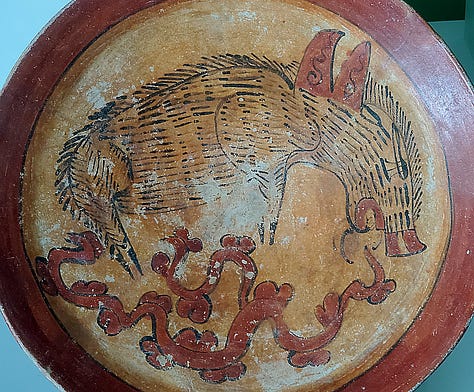

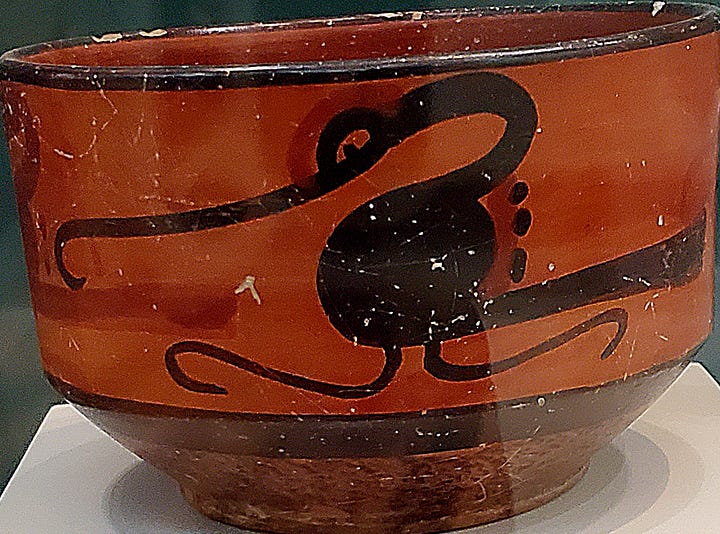

The ancient Maya also adored their birds and other fauna, needless to say:

Meanwhile, back in Pennsylvania…

…it was a good year for Northern Saw-whet Owls, with multiple probables and two confirmed pick-ups via NFC, much more than we’ve gotten in the past few years. Here’s one from 11 PM on October 7, doing a brief kew series from somewhere in the woods not far from the garage:

And here’s the best of the songs for the season, from around 5:30 AM on the improbably early date of September 12:

I have yet to pick up a decent song in three years of recording, so I’m wondering whether the pick-ups of one to five notes that the NFC sometimes detects are of individuals flying overhead?

Number 199

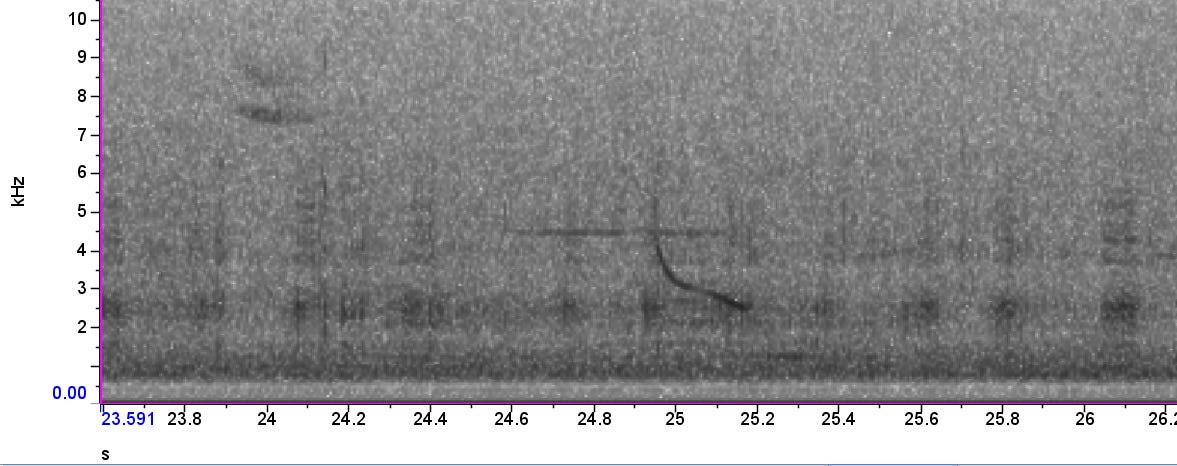

Listen carefully, and you can hear a series of teer calls (the best at 16 and 26 seconds), recording the dawn passage of a migrant Snow Bunting overhead around 6:38 AM on November 9:

Here’s what it looks like:

Not bad for a species we’ve never seen on the ground here. Blink and you’ll miss it: Plummer’s Hollow’s Snow Bunting season stretches from Nov 9 to Nov 20, based on data from 2020 to the present.

Return to Gray

And finally, some fall color to wrap things up. Again, it wasn’t great, but I’m already missing it.